ANKARA, Turkey — Turkey’s government and military leaders look determined to boost a multitude of unmanned vehicle programs in hopes these indigenous systems will serve as the backbone of future operations.

Officials and analysts say increasing asymmetrical threats on both sides of Turkey’s Syrian and Iraqi borders have urged the country’s military, procurement and industry officials to step up efforts to boost existing drone programs, or launch new ones.

“A new generation of [unmanned] vehicles — land, naval and aerial — will further strengthen our arsenal,” Ismail Demir, Turkey’s chief defense procurement official, told a conference on unmanned and robotic technologies on Feb. 22. “Those systems will earn the military strategic capabilities by providing it with intelligence imagery, fire support and ammunition transport.”

“They also will provide us with lower production, operational and maintenance costs,” a senior military official said. “More importantly, we aim to reduce personnel casualties in operations.”

At a meeting on Feb. 21, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan said: “We will carry it [indigenous drone programs] a step further. … We should attain the ability to produce unmanned tanks as well [as aerial vehicles]. We will do it.”

Erdogan’s comments came weeks after five Turkish soldiers were killed in a tank while fighting in the Kurdish enclave of Afrin in neighboring Syria.

The Turkish military launched a cross-border offensive into northern Syria on Jan. 20 to fight the emergence of a “Kurdish belt” in war-torn Syria. Turkey views that possibility as a top security threat. It has listed various Kurdish groups fighting in Syria as “terrorists,” although its NATO ally the United States largely views the groups as allies on the ground.

Strategic shift

“The paradigm shift [in favor of unmanned systems] reflects two basic motives: the military’s general tendency to catch up with the most advanced technology available, and Turkey’s perceptions of threat that are increasingly asymmetrical,” according to Ozgur Eksi, a military analyst.

Eksi said Turkey’s security-threat perceptions in the last decade have visibly shifted from conventional to asymmetrical which, along with technological change in unmanned systems, has highlighted a conceptual shift.

“The military is now devoting more time and resources to systems integration and command-and-control systems involving unmanned systems to ensure a new deployment concept, while it was in the past more interested in conventional troop and systems deployment,” he said.

One aspect of increasing unmanned deployment will be the use of special forces. “The idea is to carry out surgical operations more than before, which is a natural outcome of asymmetrical warfare,” said one Gendarmerie officer. “This comes as opposed to past warfare concepts of massive troop movements in cross-border operations.”

Turkey set up a joint special forces outpost on the Turkish side of the country’s border with Syria. Special forces from both the Gendarmerie and the police gather at this camp before they are dispatched into Syria.

“It makes perfect sense to carry out operations against asymmetrical threats with fewer troops,” the Gendarmerie officer added. “The more unmanned systems should integrate into the [military] network and more [unmanned] platforms are available for deployment, the fewer soldiers will take part in cross-border operations.”

RELATED

Confidence in industry

One procurement official familiar with unmanned systems said that in line with the availability of different drones, the work on integration and communications would gain importance.

“The success of various [unmanned] systems will depend on how successfully these systems will speak with each other as well as with command-and-control centers and manned systems,” he said. “This is an area we encourage local software companies to devote more of their time.”

Defence Minister Nurettin Canikli has acknowledged that one specific unmanned program — that of a remotely operated tank — is ”a challenging task and a very complex program. But he added that “there is a number of local companies that have the technology to make the ground work for this ambition. We think we can guide unmanned tanks by satellite connection.”

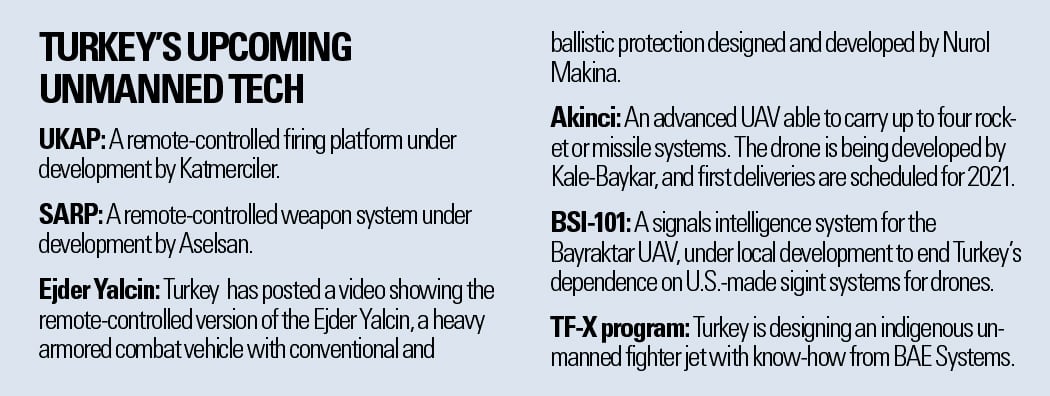

Katmerciler, a privately owned armored and anti-riot vehicles manufacturer, has been developing the UKAP, a remote-controlled firing platform. The UKAP’s missions include search and reconnaissance, radar-based target tracking, personnel rescue, mine sweeping, and towing.

The system can be remote-controlled from a maximum distance of 3 kilometers. It can operate for up to five hours on battery power, or eight hours with a power generator.

Military specialist Aselsan, Turkey’s largest defense company, showcased its SARP remote-controlled weapon system at an international defense and aerospace exhibition in Istanbul in May. The SARP features computer-based firing control functions, distance measurement, ballistic calculations and automatic target tracking.

Turkey’s procurement agency, the Undersecretariat for Defence Industries, or SSM in its Turkish acronym, recently posted a video showing the remote-controlled version of the Ejder Yalcin, an indigenous armored vehicle, during successful tests.

“Soon there will be a few autonomous vehicles in the field,” SSM’s chief, Demir, said. “More than 20 such vehicles will be used in Afrin.”

The Ejder Yalcin is a signature vehicle designed and developed by the privately owned armored vehicle-maker Nurol Makina. Nurol has sold hundreds of units of the Ejder Yalcin, a heavy armored combat vehicle with conventional and ballistic protection against mines and improvised explosive devices.

In addition to a number of unspecified foreign users, the Ejder Yalcin is used by both the Turkish military and the police special forces, mostly in the country’s southeast where Kurdish militants have been fighting a violent separatist war since 1984.

SSM officials said the first field tests for the remote-controlled Ejder Yalcin were successful.

SSM recently procured and delivered to the Army a batch of 43 remote-controlled heavy construction machines for filling holes and digging trenches. Those vehicles, controlled from a maximum distance of 1 kilometer, have been widely used in the Turkish military’s operations in Syria, SSM officials said.

Another new, ambitious program is the Akinci, an advanced UAV that can carry up to four rocket or missile systems compared to only two systems currently outfitted to the Turkish fleet of armed drones.

The Turkish government officially gave its go-ahead to the Akinci program during a meeting in January of the country’s top defense procurement panel, the Defence Industry Executive Committee, chaired by Erdogan.

The Akinci is being developed by Kale-Baykar, a private drone specialist that supplies most of the armed drones in the Turkish inventory. Compared to current models, the aircraft will have a longer endurance, carry a bigger payload and be more agile, according to procurement officials. The first deliveries of the Akinci are scheduled for 2021.

In March 2017, Kale-Baykar delivered a batch of six armed drones to the Turkish military. The Bayraktar TB2 system would be stationed in Elazig close to the Kurdish insurgency zones. Two of the TB2s are armed aircraft.

The Bayraktar uses the MAM-L and MAM-C, miniature smart munitions developed and produced by state-controlled missile specialist Roketsan.

Turkey’s local industry is also developing BSI-101, a signals intelligence system, for the Bayraktar to end Turkey’s dependence on U.S.-made sigint systems for drones.

The Bayraktar can fly at a maximum altitude of 24,000 feet. Its communications range is 150 kilometers. The aircraft can carry a payload of up to 55 kilograms.

Turkey’s defense minister said the country also plans to build an indigenous unmanned fighter jet. “We are hoping to give orders for the unmanned fighter aircraft by 2027,” Canikli said.

Turkey is designing the fighter jet with know-how from BAE Systems. The program, dubbed TF-X, awaits a governmental decision to select an engine. British engine-maker Rolls-Royce and Turkish government-controlled engine specialist Tusas Engine Industries are in a two-way race to win the engine contract.

Late last year, TEI completed the development phase of a program to build the country’s first drone engine. TEI’s PD170 went through successful initial tests, the company said. TEI has been working on the PD170 since December 2012 when it signed a development contract with SSM.

The 2.1-liter, turbo-diesel PD170 can reach 170 horsepower at 20,000 feet, and 130 horsepower at 30,000 feet. It can generate power at a maximum altitude of 40,000 feet. The PD170 was designed for the Anka, Turkey’s first indigenous medium-altitude, long-endurance drone.

Burak Ege Bekdil was the Turkey correspondent for Defense News.