A gap identified

Since Sept. 11, 2001, the United States has been heavily invested in the counterterrorism operations in Iraq and Afghanistan. This focus has largely distracted the U.S. from the changing nature of geopolitical competition and growing influence of near-peer competitors. As a result, the U.S. now faces a multipolar security environment defined by inter-state competition or “great power competition” rather than terrorism.

While the U.S. retains superiority on conventional warfare, its adversaries have found ways to indirectly compete against the U.S. in the gray zone (activities of competition and confrontation using non-traditional statecraft that fall below the threshold of armed conflict). One result has been the U.S. losing global influence; nation-state adversaries have eroded relationships the U.S. has historically enjoyed with regional powers and partners, all the while undermining the U.S.-backed rules-based liberal world order.

The U.S. is losing this war because these gray operations fall outside traditional U.S. defense strengths.

Revisionist and rogue regimes are actively using tools of irregular warfare (IW) across all instruments of national power (diplomatic, information, military, economic, political) to impose costs on the U.S. and gain influence around the world. China and Russia are using all means at its nation’s command, short of war, to achieve its national objectives.

As gray zone operations increase and evolve, the U.S. must use lessons learned from the Cold War and ensure whole-of-government solutions are developed that incorporate the unique capabilities of our agencies and departments. Presupposing a whole-of-government strategy, the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) plays a supporting role in great power competition. To compete in active and ongoing gray zone operations, the DoD should systematically employ its special operations forces (SOF).

SOF superiority

SOF are an agile force with a small footprint uniquely positioned in over 100 countries capable of operating in all domains with allied and partner forces. The SOF community works “by, with, (and) through” foreign security elements in pursuit of U.S. interests, investing in willing and capable partners to promote U.S. influence and align political objectives with these efforts. With SOF’s unique training to operate in contested security environments, unclassified vignettes have highlighted SOF’s successes in combatting adversarial gray zone operations.

At the operational level, military commanders have been stretched thin between using SOF for ongoing counterterrorism (CT) and stability operations, while also strategizing the doctrinal and resource adjustments needed to address the growing influence of inter-state conflict. The narrow CT mission set of the past 20 years has atrophied core activities of the SOF skills and capabilities. U.S. Special Operations Command (USSOCOM) must focus the SOF “forces of tomorrow” on an alignment to achieve U.S. political outcomes, reinforce doctrinal mission sets of influence and legitimacy, and rebalance the core activities of SOF.

Political warfare

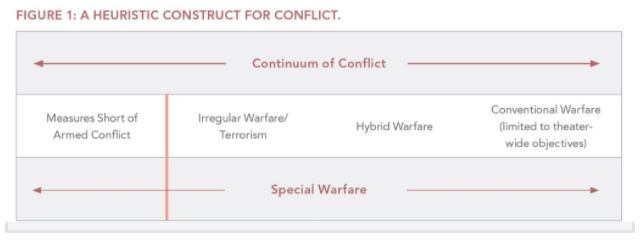

Political warfare is the use of political means to compel an opponent to do one’s will. As Chairman Dunford of the Joint Chiefs of Staff admitted, “We’re already behind in adapting to the changed character of war today in so many ways.” The U.S. national strategy towards great power competition must acknowledge that the binary peace/war distinction is erroneous, and instead approach conflict as a continuum, or a range of different modes of conflict (figure 1). The U.S. has failed to recognize and engage optimally with the realities of great power competition and its ability to sustain incentives for partner nations and its right to lead, resulting in China and Russia dividing the rules-based international order.

Source: National Defense University

The role of SOF

The recently published Irregular Warfare Annex calls on the DoD to increase SOF’s emphasis on unconventional warfare capabilities to support IW in pre-conflict and conflict phases against China and Russia. The Joint Concept for Integrated Campaigning recognizes the myriad ways that the threat of violence can and should be used in a number of competitive realms to strike a balance between the typical operational doctrines and unstructured opportunism of an adversaries’ gray zone operations. By utilizing SOF’s unique access and 10 core activities, SOF can develop resilience in indigenous populations and use its IW asymmetric advantages to counter gray zone operations. The increased bandwidth afforded by SOF’s decreased focus on CT will ensure the DoD is better positioned to compete in the gray zone alongside inter-agency assets and redirect to steady-state activities against near-peer opponents.

Policy recommendations

The DoD should leverage SOF’s successes in IW to rebalance missions to meet the full range of new and emerging security challenges and support a comprehensive campaign in great power competition.

Policymakers need to create and implement a new conceptual framework utilizing SOF as part of an overall strategy for combatting great power adversaries.

The DoD and USSOCOM must prepare a strategy to operationalize great power competition, which accepts that victory does not belong to the strongest army but the best practitioner of the operational art of the strategy. While preparation for a conventional war against a great power serves as a deterrence strategy, the DoD strategy must broaden the U.S. definition of competition and diversifying our policy toolkit for multiple response options before reaching the point of escalation of force.

While Department of State is the lead on bilateral relationships, the DoD can assist in pursuing complementary diplomacy with partners and allies by expanding the Combatting Terrorism and Irregular Warfare Fellowship Program (CTIWFP).

The DoD should prioritize and expand the CTIWFP which serves as an instrument of influence by reinforcing U.S. values and establishing military to military relationships which will prove indispensable in the long-term.

U.S. Special Operations Command and assistant secretary of defense for special operations/low intensity conflict should implement a heat map to identify overlapping areas of great power competition to coordinate the joint forces.

DoD leaders must think beyond the stovepiped global geographic combatant command map to identify overlapping areas of great power competition. A more holistic approach to combatting adversarial gray zone operations means implementing a heat map of where great power competition is taking place, which would allow the combatant commands and USSOCOM to synchronization in joint force operations.

Special operations forces are not the silver bullet solution: policymakers must use the joint force, including conventional forces, as one among several tools to be utilized in great power competition.

Just as great power competition requires a whole of government approach, the entire conventional force must contribute to these non-combat efforts with skills already in its ranks. The Commandant Planning Guidance document issued by General Berger in 2019 lays out a new vision for the Marine Corps; the Marines implemented the Marine Expeditionary Force Information Group, bringing cyber, information warfare, and electronic warfare to the conventional forces which will support information warfare in gray zone operations.

SOF recruitment must reprioritize new skills such as language proficiency, cyber, intelligence, engineering, and cultural studies as U.S. Special Operations Command rebalances its forces away from the counterinsurgency and counterterrorism skill sets utilized in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Missions in support of great power competition gray zone operations will fall below the level of the direct-action armed conflict that defined SOF for the past 20 years. USSOCOM must prioritize recruitment focused around language skills, engineering, cyber, intelligence, and cultural skills as the SOF forces are rebalanced in support of great power competition.

Specific congressional authorities are needed for U.S. Special Operations Command to effectively use SOF in great power competition.

• Congress should raise the Section 1202 funds (FY18 National Defense Authorization Act, Public Law 115-91), Authority for Support of Special Operations for Irregular Warfare, above the $10 million ceiling to account for expanded mission sets in support of great power competition.

• Congress should appropriate funds directly to USSOCOM for humanitarian assistance funds for training foreign forces. This would greatly expand the current toolkit SOF can use to counter gray zone operations.

• Title 10 U.S. Code 127e, Support Special Operations to Combat Terrorism should be modified to allow the unused funds ($100M per fiscal year) to roll over or be reprogrammed to support SOF mission sets for great power competition. Currently, Congress appropriates $100 million annually for 127e operations.

Initiate a Strategic Level Information Coordination Center for Developing and Coordinating U.S. Response to Near-Peer Influence Campaigns.

The FY21 House Appropriations Committee Report recognizes the importance of Military Information Support Operations as the SOF shifts from information operations against non-state to state actors. To fuse efforts within the DoD as well as the Department of State’s Global Engagement Center, a strategic level Information Coordination Center should be established to coordinate all U.S. government information operations and should include the CIA, USSOCOM, NSA, National Geospatial Agency, and USAID.

President-elect Biden’s Secretary of Defense should elevate ASD SOLIC to an undersecretary of defense, strengthening civilian oversight of USSOCOM.

• Sec. 922 of the FY17 NDAA mandated the DOD transition the ASD SOLIC to an Undersecretary of Defense, reporting directly to the Secretary and Undersecretary of Defense. On Nov. 18, 2020, Acting Secretary of Defense Christopher Miller designated ASD SOLIC a principal staff assistant, removing SOLIC from the undersecretary of defense for policy construct. This does not go far enough. The next secretary of defense should fulfil the intent of Congress and elevate SOLIC to an undersecretary position to provide executive-level oversight over the military culture, direct budget authorities, and shape the future SOF force to counter near-peer adversaries.

• The incoming Biden administration must prioritize the confirmation of the next ASD SOLIC to drive the needed paradigm shift and provide consistent civilian oversight. The last Senate-confirmed ASD SOLIC departed the DOD on June 22, 2019, and five acting ASD’s have been in the position since.

Conclusion

The U.S. is at an inflection point: if it fails to acknowledge and counter asymmetric gray zone operations against its adversaries, the cost to regain its advantage and global military superiority will be greatly increased. Failure to adjust to asymmetric challenges forfeits the U.S.’s ability to proactively control the competition space. Therefore, the DoD must be introspective and ensure that the forces of tomorrow will be right-sized with appropriate doctrinal mission sets to compete against near-peer adversaries with an interagency political warfare strategy to impose costs and control the narrative.

Kaley Scholl is a student at the Johns Hopkins School for Advanced International Studies’ Masters of Global Policy program. She currently works in congressional affairs for the assistant secretary of the Navy for research, development and acquisitions. She holds a bachelor’s in cultural anthropology and a master’s in education from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

The views expressed in this report are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of Defense or the U.S. Government. Authors of Johns Hopkins University publications enjoy full academic freedom, provided they do not disclose classified information, jeopardize operations security, or misrepresent official U.S. policy. Such academic freedom empowers them to offer new and sometimes controversial perspectives in the interest of furthering debate on key issues.

Editor’s note: This is an Op-Ed and as such, the opinions expressed are those of the author. If you would like to respond, or have an editorial of your own you would like to submit, please contact Military Times managing editor Howard Altman, haltman@militarytimes.com.