Conventional wisdom says it would be over quickly: China would bring overwhelming military power to bear against Taiwan, and the island would quickly capitulate. But wars are unpredictable things; they seldom go as planned. The possibility of a protracted Taiwan fight – like the kind Ukraine is waging now – should not be overlooked.

And in such a scenario, the logistics of resupplying the isolated island – especially its potential insurgents – would be vital to restoring the status quo. What’s more, a credible capability to deliver sustained food, aid, and weapons could well complicate Beijing’s decision calculus enough to deter an attempted invasion in the first place.

RELATED

U.S. defense planners should place a high premium on innovative solutions for doing just that, especially as present resupply challenges do not inspire confidence. The Philippines, for example, is currently facing extreme difficulties resupplying its far-flung outposts due to Chinese interference in an ostensibly peacetime environment. With China’s land-based missiles able to sink surface ships 4,000 kilometers out to sea, with its land-based fighters significantly outnumbering U.S. and allied aircraft, it is imperative to think outside the kill box and reassess the potential roles played by submarines.

Beyond their traditional use in naval power projection and intelligence gathering, submarines offer a far more survivable means for delivering sustained vital supply lines to isolated islands, whether Taiwan, U.S. bases, or other partners.

A little discussed history shows this to be the case, but it’s recent developments in autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) that could prove the point well enough to make a difference now. War creates extreme necessity amongst combatants, and as all know, necessity is the mother of invention.

The submarine as a resupply vehicle

The idea of using submarines as transport vessels dates back to the 19th century. However, the Royal Navy’s strangling blockade of Imperial Germany during World War I moved theory into reality. Beginning in 1914, Britain declared the North Sea a war zone, forbade American trade, and instituted a blockade that quickly exhausted Germany’s small supply of critical raw materials. Facing a protracted war and unable to conduct trade with surface vessels, Germany resorted to building unarmed submarines as clandestine merchantmen.

The most famous of these was the submarine Deutschland which made two successful commercial voyages to the U.S. in 1916 – returning with over 700 tons of nickel, tin and rubber for the German war effort. The two voyages proved incredibly profitable, as the cargo was worth several times the submarine’s construction costs.

Despite Deutschland’s success, the victorious Allies quickly forgot the value of submarine resupply during the interwar period. The U.S. Navy was unprepared for the Japanese invasion of the Philippines in 1941 and failed to enact its prewar plans for the island chain’s resupply due to the losses suffered at Pearl Harbor. A similar scenario could well confront the Navy should China launch a preemptive strike on U.S. bases in the Pacific as prelude to an invasion of Taiwan.

What followed in early 1942 was a period of improvisation often overlooked in the history books. Reluctant to risk surface ships, the Navy successfully sent eight different fleet submarines to resupply besieged American forces in the Philippines from mid-January to early May 1942. These missions – all successfully executed under the noses of the Japanese – delivered 17 tons of vital foodstuffs, 36 tons of anti-aircraft shells, millions of rifle-caliber small arms cartridges, and hundreds of gallons of critical diesel fuel for Corregidor’s generators. They also evacuated 185 personnel essential to the war effort. The success of this effort – borne of necessity during the hour of peril – was soon forgotten, however.

Surprisingly, the narco cartels of Latin America are responsible for the most significant developments in submarine-based logistics since the end of World War II. Beginning in the early 2000s, the cartels were forced to improvise due to the U.S. Coast Guard’s increased prowess in intercepting surface traffic. Simply put, the cartels chose to go under, rather than over the water. These narco-submarines are custom-built, self-propelled vessels designed to smuggle drugs while minimizing their visual and radar profiles.

The most recent are nearly fully submersible and can avoid detection by visual, radar, sonar, and infrared systems. While cargo capacity varies with the size of the vessel, a load of several tons is typical. In 2019, the USCG seized one such craft carrying 8.5 tons of cocaine – the largest confirmed cargo of a semi-submersible thus far. Much like the Deutschland a century ago, a single successful voyage generates enough income to completely fund all the costs of building and manning a narco-submarine. Emboldened by the potential profits, the cartels are beginning to construct contemporary narco-submarines that are true submersibles – ones capable of crossing the Atlantic Ocean.

Lessons for 2023

With the possibility of a looming Chinese invasion of Taiwan, the U.S. Navy and Merchant Marine should examine the possibility of using submarines, UAVs, or unmanned semi-submersible vessels as a means of resupply in event of a blockade. Such efforts could provide a mechanism for supplying critical items, for example, Javelin and Stinger missiles.

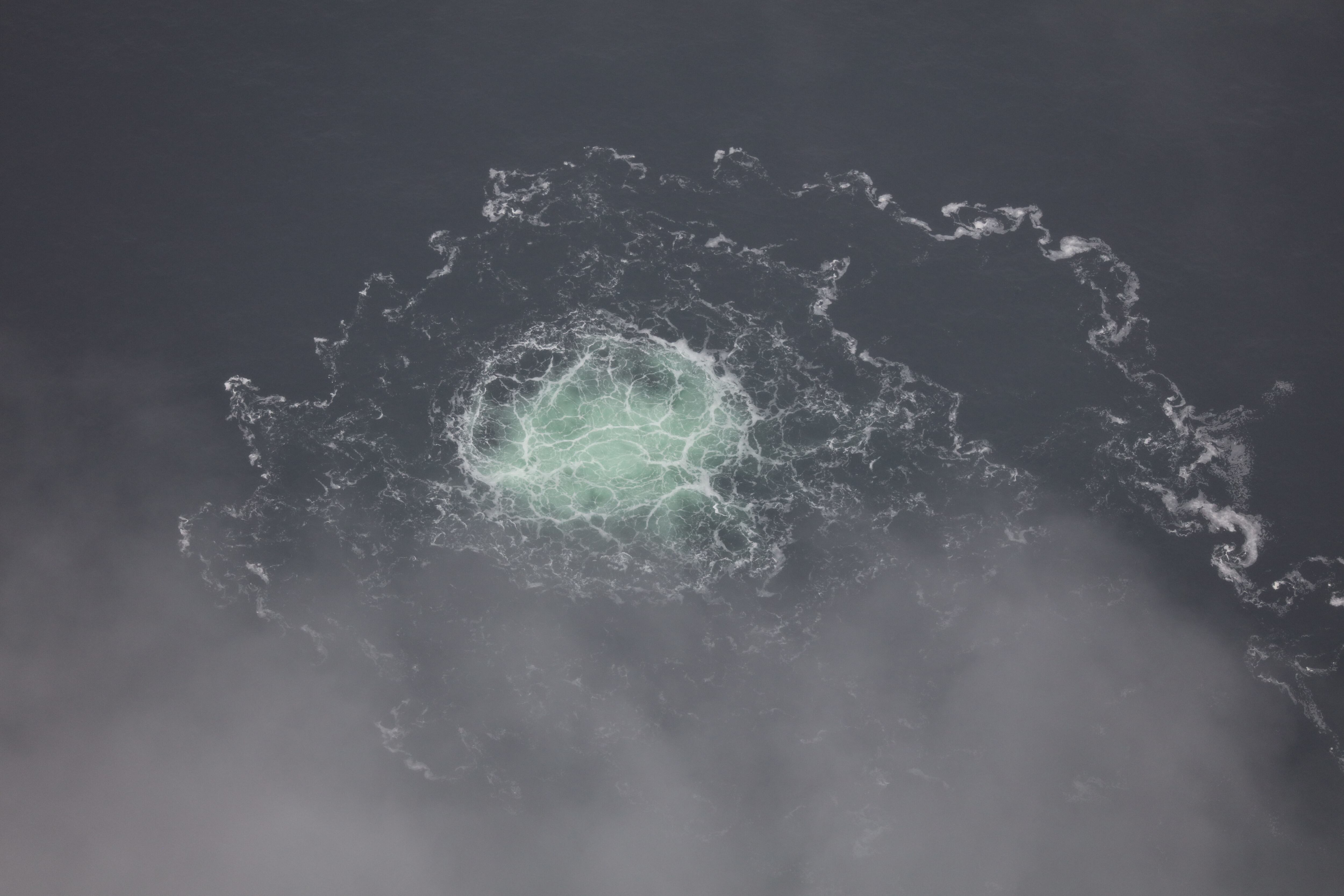

The Ukrainian Navy has already demonstrated the impact of autonomous submersible drones to attack Russian shipping in the Black Sea. If enlarged and repurposed for logistical resupply, similar craft could present a high chance of success at a low cost in the Indo-Pacific. Most importantly, such systems would not place U.S. or allied personnel at risk.

Sub-surface assets have the potential to offer a game-changing alternative for delivering critical resources when surface routes are compromised. The strategic advantages of incorporating submarines into resupply operations – their ability to navigate undetected, evade hostile forces, and ensure the uninterrupted flow of essential goods to partners in times of crisis – cannot be ignored.

The U.S. should invest accordingly.

Bill Rivers is a fellow at the Yorktown Institute. He served as speechwriter for U.S. Secretary of Defense Jim Mattis from 2017-19. Matt DiRisio is a logistics officer in the U.S. Army and previously served as an Assistant Professor at the U.S. Military Academy. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of the U.S. Military Academy or the U.S. Army.