In an excerpt from the essay collection “Strategy Strikes Back: How Star Wars Explains Modern Military Conflict,” Dan Ward looks at patterns of virtuous simplicity and evil complexity in a galaxy far, far away, and how this relates to today’s battlefield.

In 1977 “Star Wars: Episode IV-A New Hope” introduced lightsabers to the world in a quietly poignant scene. Half an hour into the film, we see an old hermit named Ben Kenobi pass along an antique family heirloom to an orphan boy named Luke. Old Ben describes the weapon in downright poetic language. He wistfully explains that the obsolete artifact is “an elegant weapon, for a more civilized age,” clearly implying that particular age came to an end a long time ago.

The moment Luke switched the lightsaber on and waved the glowing beam back and forth began a long-standing love affair with this simple glowing blade. A 2008 survey by 20th Century Fox (three decades after “A New Hope” was released!) selected the lightsaber as the “best weapon ever featured in a movie,” beating out Dirty Harry’s handgun (No. 2) and Indiana Jones’s bullwhip (No. 3). In case you’re wondering, the Death Star came in at No. 9.

The thing that is so right and so appealing about the lightsaber is its simplicity. In the hands of a trained Jedi (or, frankly, a half-trained Jedi), this single beam of energy demonstrates a wide range of capabilities: deflecting blaster shots, cutting through reinforced bulkheads, and delivering some of the most dazzling swordplay ever filmed. It is a knight’s weapon, graceful and sophisticated. There is something pure and good in its clean lines and unpretentious structure.

As the saga continues, viewers discover that Jedi are not the only ones in this far, far away galaxy who use such elegant weapons. Villains use them too. Throughout the original trilogy, good guys and bad guys use essentially identical lightsabers. Only the color distinguishes noble Jedi Knights from malevolent Sith lords. But in the prequel trilogy and the sequel trilogy, we begin to see design variety among these glowing, buzzing weapons. That’s where things get interesting and begin to reveal something important about complexity and combat effectiveness.

RELATED

When a Sith lord named Darth Maul appeared in “Episode I-The Phantom Menace,” he instantly captivated audiences by wielding a double-sided lightsaber. This was the first variation shown to a wide audience (not counting the various light-weapons in “Star Wars” comics or “Clone Wars” cartoons). We were all suitably impressed by the ferocity of Darth Maul’s acrobatic combat skills, and there was something undeniably cool about his weapon of choice. However, he was no match for young Obi-Wan, who first sliced the weapon’s hilt in half and then sliced its user in half to match. So much for double-sided sabers.

Fast-forward to “Episode VII-The Force Awakens.” When the trailer was released, fans around the world went crazy over Kylo Ren’s cross-hilted lightsaber. Sure, Darth Maul used two blades at once, but this new, mysterious weapon had three! What did it mean? How would it work? Let us set aside for a moment the discussion over Darth Tantrum’s emotional maturity level and dubious combat skills, or even the effectiveness of his unique weapon. Instead, take a moment to notice the pattern that is beginning to emerge: Jedi rely on elegant, single-bladed sabers, while those who follow a darker path adopt weapons of increasing complexity. Spoiler alert: the added complexity does not help. The bad guys still lose.

As further proof of the dark side’s tendency to ineffectively add complexity to the elegant Jedi weapon, consider the four-armed asthmatic cyborg named General Grievous from “Episode III-Revenge of the Sith.” Naturally, he wields four lightsabers at once. In his metal hands they essentially become four parts of a single weapon. But big surprise, the extra blades don’t help him any more than they helped Darth Maul. Obi-Wan beats him too.

Something profound is happening here, with real-world parallels and applications. We see a tight correlation between a tendency toward evil and a preference for complexity. The upright Jedi who follow the light side are dedicated to the simplicity of a single blade. The evil Sith, in contrast, continue making things more complicated.

Darth Vader, the most fearsome of the Sith lords, is a notable exception. True to his Jedi heritage (and perhaps foreshadowing his — spoiler alert! — eventual redemption) he wields a simple, single-bladed weapon and does so to great effect. His brief fight scene in “Rogue One” is a particularly chilling demonstration of his ruthless efficiency and helped to cement his position as one of the greatest movie villains ever.

The same pattern of virtuous simplicity and evil complexity shows up in virtually every battlefield in the “Star Wars” universe. The bad guys rely on large, complicated weapons and are defeated by good guys using smaller, simpler tools.

From a storytelling perspective, there is something appealing about situations where a small, virtuous protagonist beats a big, evil adversary. This concept is as old as the biblical story of David and Goliath and as contemporary as Malcom Gladwell’s 2013 book “David and Goliath.” But there is something even more profound happening. The idea that simplicity prevails over complexity is not just a nice romantic notion. It is also a concept that is constantly borne out in real-world battlefields.

In a widely disseminated 2007 paper titled “Nothing’s Too Good for Our Boys,” military analyst Pierre Sprey famously observed, “Not all simple, low-cost weapons work. However, war-winning weapons are almost always simple.” His paper went on to compare combat performance data for a wide range of weapon systems, from rifles and aircraft, tanks and missiles. In every case, there was a direct relationship between low-cost simplicity and superior performance. Sprey concluded his analysis by dividing weapons into two familiar categories: cheap winners and expensive losers. Jedi clearly prefer the former category, while Sith gravitate toward the latter.

History provides many similar examples of this dynamic in play. At the Battle of Agincourt in 1415, a numerically superior force of French knights in heavy plate armor was famously defeated by English forces led by Henry V. The muddy terrain was a significant contributor to the outcome, but the English longbow is widely credited with contributing decisively to the victory. The longbow, it should be noted, was considerably cheaper, lighter, and simpler than the crossbow favored by European armies, to say nothing of the cost and complexity of a full suit of armor. The Battle of Endor was basically a reenactment of Agincourt, in which the English were played by Stone Age teddy bears.

Other analyses, in genres far beyond military technology, have reached identical conclusions about the way complexity reduces system effectiveness. A program management research firm named the Standish Group analyzed hundreds of IT development projects and identified a stark contrast between “Winning Hand” projects (which embraced speed, thrift, and simplicity) and “Losing Hand” projects (which were deliberately slow, expensive, and complicated). They used different category labels than Sprey, but their conclusion is essentially identical. Spending more time and money does not improve quality or boost performance. Neither does allowing complexity to rise. Instead, as the cost, schedule, and complexity of a system increases, the likelihood of catastrophic failure rises proportionally, resulting in projects that cost more, take longer, and deliver less than promised.

These data suggest that there are several reasons “Star Wars” scriptwriters and prop designers give simple weapons to the good guys and complex weapons to the bad guys. In part, this is because they want the bad guys to look imposing (see Goliath). They want to add drama to the story, and they know there is nothing more impressive and dramatic than a moon-sized battle station or four lightsabers being twirled by a cyborg. But there is another, deeper reason.

The one thing these stories need more than a daunting villain is ... a victorious protagonist. The “Star Wars” writers want the good guys to win in the end; and for their triumph to be dramatically satisfying, it must be convincing. Every storyteller knows that the best fiction is built on a foundation of truth; so to ensure that the good guys convincingly come out on top by Act 3, the filmmakers decided to give them the most effective weapons and to stick the villains with weapons that were merely intimidating. Thus, the protagonists got single-bladed lightsabers. A bucket-of-bolts, hunk-of-junk cargo ship. Single-seat X-wing fighters. And don’t forget R2-D2, a droid without a face or voice who managed to nevertheless demonstrate a genuine personality and who was once described by George Lucas as “the hero of the whole thing.”

In film and on the battlefield, in fiction and in real life, the most effective designs express a clear preference for thrift and simplicity. The lesson for modern military technologists is clear: minimize complexity. Exercise restraint. The “Star Wars” films are not just telling a David and Goliath story because it’s dramatic or entertaining. They’re doing so because it is true, a lesson today’s militaries would do well to remember.

Also, the Empire should stop building Death Stars. Those things keep getting blown up.

From the author’s chapter in “Strategy Strikes Back: How Star Wars Explains Modern Military Conflict,” edited by Max Brooks, John Amble, ML Cavanaugh, and Jaym Gates. Used by permission of the University of Nebraska Press and its imprint Potomac Books. © 2018 by Max Brooks, John Amble, ML Cavanaugh, and Jaym Gates

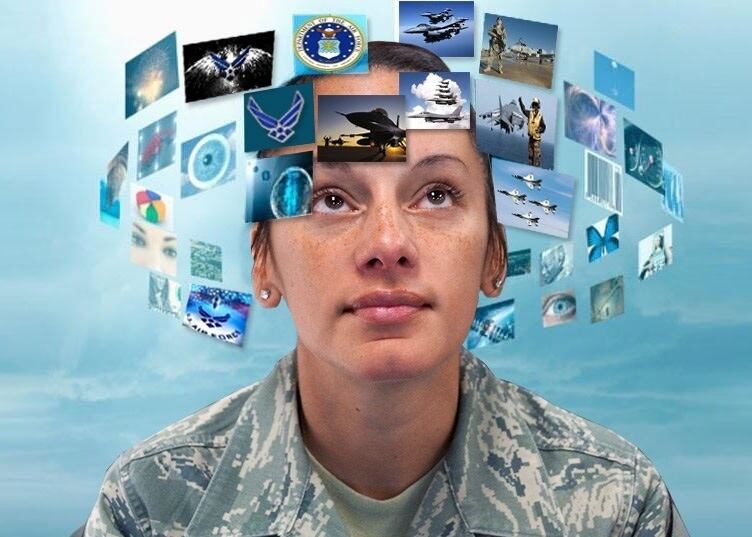

Dan Ward is the author of “The Simplicity Cycle: A Field Guide to Making Things Better without Making Them Worse” (New York: HarperCollins, 2015) and “F.I.R.E.: How Fast, Inexpensive, Restrained, and Elegant Methods Ignite Innovation” (New York: HarperCollins, 2014). He served in the U.S. Air Force and retired at the rank of lieutenant colonel. Dan holds three engineering degrees and received the Bronze Star for his service in Afghanistan.