The Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory recently grabbed international attention with its announcement that experiments there hit a milestone in nuclear fusion research that’s dogged scientists for decades.

But what’s less commonly known about the laboratory, called the “Rad Lab” for its work on radiological technology, is that it developed some of the most important advances in nuclear science since its founding 70 years ago.

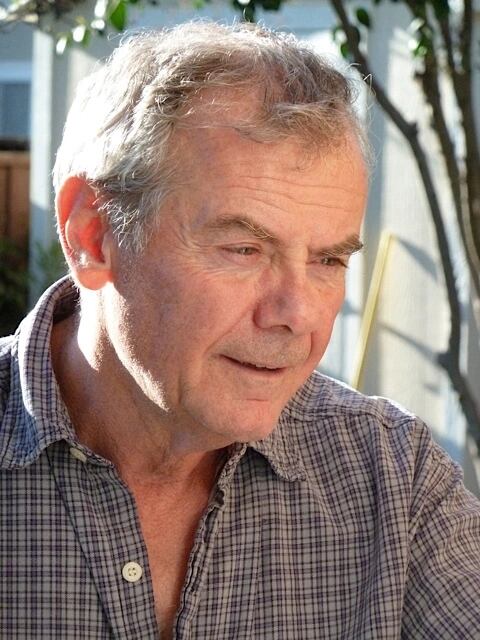

And for 40 of those years, Tom Ramos has worked as a physicist at the laboratory, part of the team that developed the X-ray Laser for President Ronald Reagan’s Strategic Defense Initiative and other technological achievements.

This year Ramos published a book that gives a detailed, inside history of the laboratory and specifically focuses on how work at the laboratory contributed to technologies that allowed then-President John F. Kennedy to stare down the Russian political and military leadership early in the Cold War.

No, not the Cuban Missile Crisis, though that was likely affected, too. An earlier event, the Berlin Crisis of 1961, was Kennedy’s first nuclear-driven challenge against the Soviet Union.

In mid-August 1961, East German officials closed the border and directed by Soviet leaders put up what would become The Berlin Wall, cutting East and West Berlin off from each other.

Then-Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev threatened the use of nuclear weapons if the United States intervened.

By October 1961 the standoff had escalated to the point that U.S. and Soviet tanks were positioned 100 yards apart at Checkpoint Charlie, a now-infamous Berlin Wall crossing point between East and West Berlin.

What the public didn’t know and would not be revealed in detail until years later was that leaders on both sides were weighing the use of nuclear weapons. Kennedy called Khrushchev’s bluff and the Soviets backed down.

The episode served as a kind of dry run, with its own very dire consequences, of the more widely known, Cuban Missile Crisis in October 1962.

Ramos discovered through his research in the archives of the Livermore laboratory that Kennedy traveled to Livermore and personally thanked scientists at the installation for the technological breakthroughs, including the Polaris missile, a submarine-launched weapon developed by the Livermore lab.

That weapon allowed Kennedy to have nuclear weapons within striking distance of the Soviet Union at the time.

Ramos talked with Military Times about his book, “From Berkeley to Berlin: How the Rad Lab Helped Avert Nuclear War.”

Editor’s Note: This author Q&A has been edited for length and clarity.

Q: What drove you to research and write this book?

A: Back in the 1980s I’d written a 300-page history of the X-Ray Laser program, the Star Wars program that I’d been a part of on the design team. I’d shared that with our associated director a few years ago and offered to start writing a history of the Robin program, a small, more efficient nuclear warhead initiative started in the mid-1950s. As I was researching, I realized you couldn’t really understand what the scientists were doing at the time unless you went back further. Such questions as, why was the Lawrence Livermore Laboratory created in the first place? I really got intrigued by what I was digging into. I took every single nuclear test the laboratory had conducted since its beginning and looked at why did they conduct that test and what were the results? I learned about Kennedy’s visit, and I talked with Michael May, the lead physicist on the team that Kennedy came to thank for helping avert nuclear war. I asked him what it was like. He said Kennedy walked into the lobby doors with a big smile on his face, came across the floor, stuck out his hand and said, “Thank you so much.” May said it was the proudest day of his life. And I said, this is a story I’ve got to write about, and I got passionate about what these people have done back in the 1950s.

Q: Your book focuses on the Berlin Crisis of 1961 and the laboratory’s connection to it. Why was that event so important in the history of nuclear weapons development?

A: My research started unraveling how Kennedy’s access to the Polaris warhead, a mobile, submarine-launched weapon, gave him the ability to stand up to Khrushchev’s moves in Berlin. And I learned that achieving that military dominance for Kennedy was not easy, it was a challenge. There were experts at the time who said that the United States achieving military and technological dominance over the Soviet Union was nearly impossible. So, the gist I tried to portray in the book was these guys, and a few women, mostly 20 and 30-year-olds, had a challenge. They designed a thermonuclear warhead that was three times smaller than the smallest one that had ever existed. That allowed the Navy to put these warheads on submarines and gave the U.S. military mobility and reach for weapons they could put wherever they needed to strike.

Q: The Livermore has notched some major achievements, but many people would be hard-pressed to recognize it by name, whereas the Los Alamos laboratory still has some name recognition. What should readers know about the Livermore lab?

A: To me, a story must have a hero to accomplish a goal. The lore that I was told when I arrived at this laboratory was that it was created by Edward Teller so he could build hydrogen bombs. And everyone accepted that. But through my research, I realized no, that’s not true. The real hero who’s most responsible for all of this I learned was Ernest O. Lawrence. Historians treat him very badly; they treat him like a country bumpkin. But I realized what Lawrence accomplished was phenomenal as an experimental physicist, he’s one of the greatest of the 20th Century.

Q: What can readers learn today from both the Berlin Crisis and the 70 years of work that’s been done at the laboratory that pertains to current events?

A: Starting in the early 1990s with the Nuclear Test Ban Treaty, Congress forbids any funding for any testing or work on new nuclear weapons at the laboratory. Before this, I spent 10 years of my life on interesting ideas that had a profound effect on the Cold War. But now we’re facing, a much more belligerent China and now Russia coming up and they throw around the nuclear word. The question is, how do we handle these nuclear states? And the answer is, we’re not prepared for that. I’m not going to say anything classified, but for example, you make a warhead and the thing that starts it off is an atom bomb, and that has a high explosive. A high explosive is acidic. Put it against metal, put it in a box having been exposed to humidity, etc. and let it sit for 50 years. That’s the state of our nuclear stockpile. Each year our stockpile gets one year older. Regardless of how much science and how much people say to Congress, “We’re ready,” the reliability of our strategic deterrence can’t be as high as it was 30 years ago.

Correction: This article has been updated to correctly identify the name of Ernest O. Lawrence, a nuclear scientist.

Todd South has written about crime, courts, government and the military for multiple publications since 2004 and was named a 2014 Pulitzer finalist for a co-written project on witness intimidation. Todd is a Marine veteran of the Iraq War.