COLOGNE, Germany — In the illustrious history of the F-35 fighter jet, add a pony farm outside Berlin as the place where one company claims the plane’s stealth cover was blown.

The story that follows is a snapshot in the cat-and-mouse game between combat aircraft — designed to be undetectable by radar — and sensor makers seeking to undo that advantage. In the case of the F-35, the promise of invisibility to radar is so pronounced that it has colored much of the jet's employment doctrine, lending an air of invincibility to the weapon: The enemy never saw it coming.

But technology leaps only last so long, and Russia and China are known to be working on technology aimed at nixing whatever leg up NATO countries have tried to build for themselves.

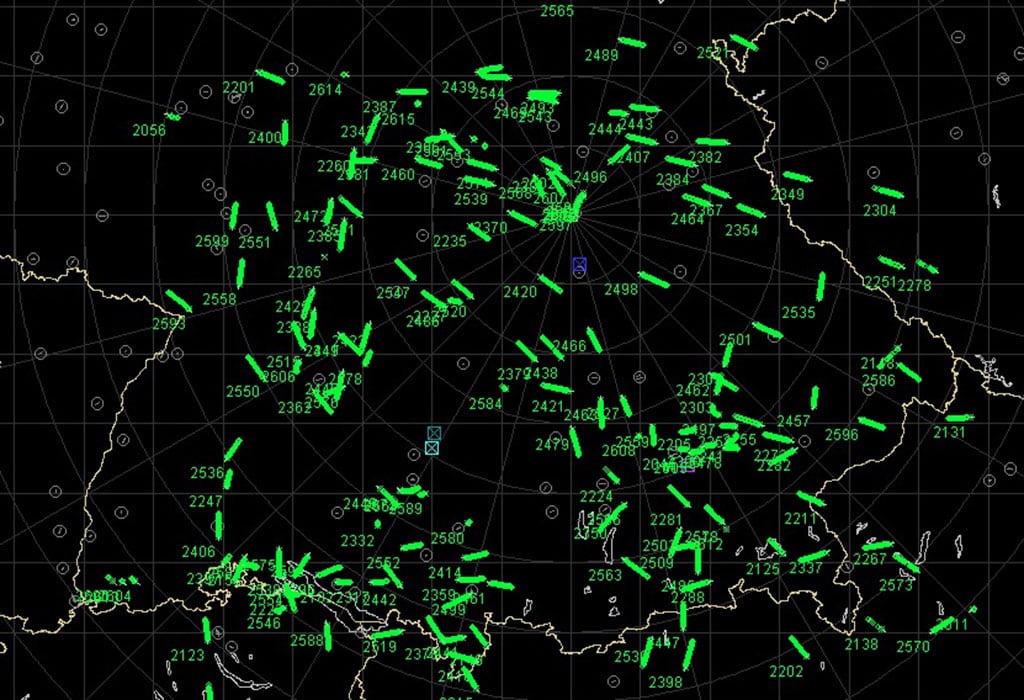

Now, German radar-maker Hensoldt claims to have tracked two F-35s for 150 kilometers following the 2018 Berlin Air Show in Germany in late April of that year. The company’s passive radar system, named TwInvis, is but one of an emerging generation of sensors and processors so sensitive and powerful that it promises to find previously undetectable activities in a given airspace.

What happened in Berlin was the rare chance to subject the aircraft — stealthy design features, special coating and all — to a real-life trial to see if the promise of low observability still holds true.

Stories about the F-35-vs.-TwInvis matchup had been swirling in the media since Hensoldt set up shop on the tarmac at Berlin’s Schönefeld Airport, its sensor calibrated to track all flying demonstrations by the various aircraft on the flight line. Media reports had billed the system, which comes packed into a van or SUV and boasts a collapsible antenna, as a potential game changer in aerial defense.

At the same time, F-35 manufacturer Lockheed Martin was still in the race to replace the German Tornado fleet, a strategically important opportunity to sell F-35s to a key European Union member state. The company set up a sizable chalet at the air show, bringing brochures and hats depicting the aircraft together with a German flag.

Showtime in Schönefeld

The most convincing pieces of marketing for Hensoldt were meant to be two F-35s flown in from Luke Air Force Base, Arizona. The trans-Atlantic journey marked the jets’ longest nonstop flight, at 11-plus hours, officials said at the time.

But Lockheed and the U.S. Air Force did not fly the jets during the show so that its engineers — and anyone walking by the company’s booth, for that matter — could see if the aircraft would produce a radar track on a big screen like the other aircraft.

Reporters never got a straight answer on why the F-35s stayed on the ground. One explanation was that there was no approved aerial demonstration program for the aircraft that would fit the Berlin show’s airspace limitations.

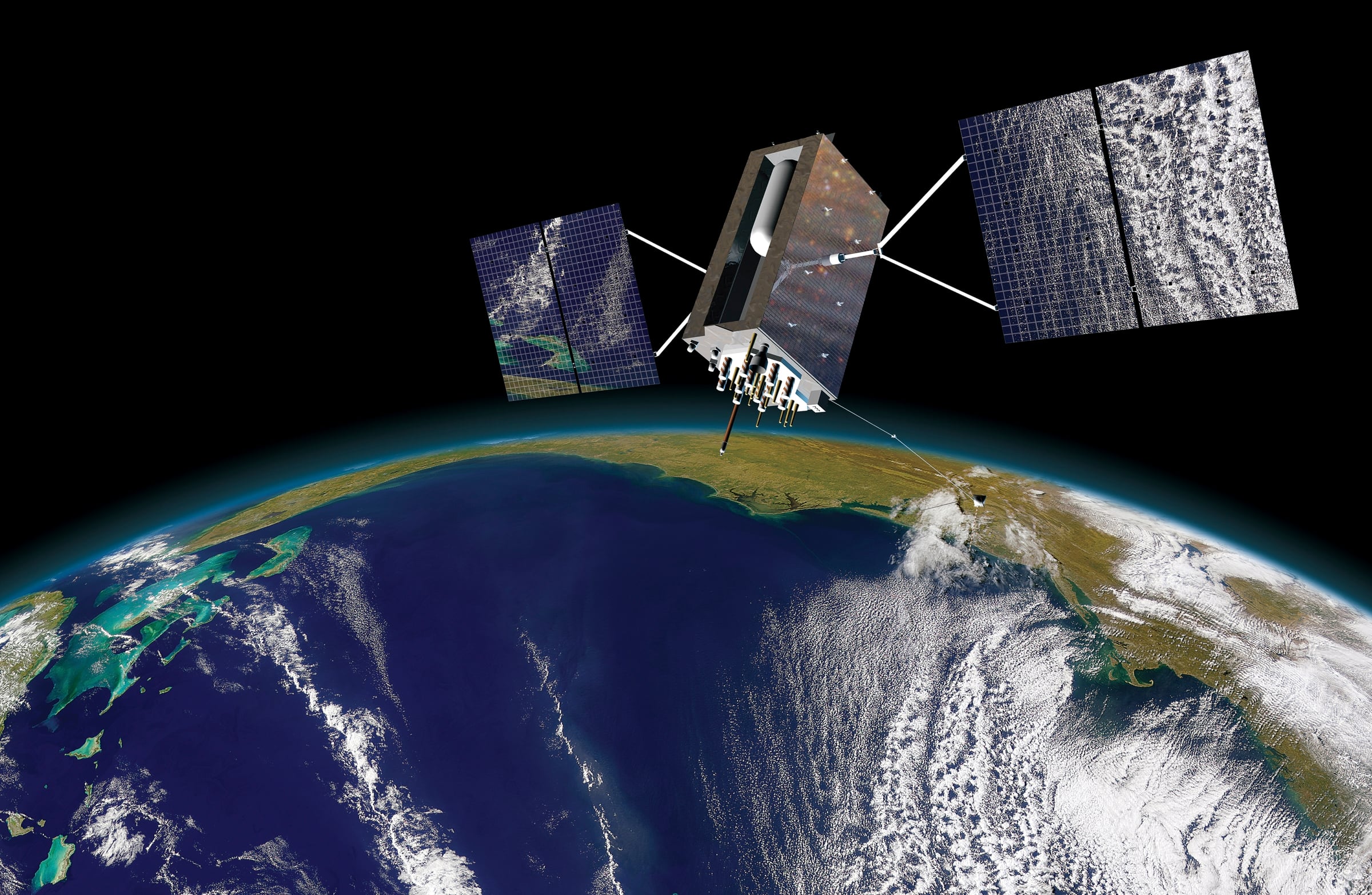

Regardless of the reason, with no flight by the F-35, companies could not try out their technologies on perhaps the most illustrious of test cases. Passive radar equipment computes an aerial picture by reading how civilian communications signals bounce off airborne objects. The technique works with any type of signal present in airspace, including radio or television broadcasts as well as emissions from mobile phone stations. The technology can be effective against stealthy aircraft designs, which are meant to break and absorb signals from traditional radar emitters so that nothing reflects back to ground-station sensors, effectively leaving defensive-radar operators in the dark.

Because there are no emitters, passive radar is covert, meaning pilots entering a monitored area are unaware they are being tracked.

There are limitations to the technology. For one, it depends on the existence of radio signals, which may not be a given in remote areas of the globe. In addition, the technology is not yet accurate enough to guide missiles, though it could be used to send infrared-homing weapons close to a target.

Hensoldt said various radio station broadcasts in the area, especially a bunch of strong Polish FM emitters broadcasting deep into Germany, improved TwInvis calibration during the Berlin show. The border is about 70 kilometers away from Schönefeld Airport.

During a system demonstration by Hensoldt at the exhibit, company engineers convened around a large TwInvis screen showing the track of a Eurofighter performing a thundering aerial show nearby. But the prized target of opportunity, the two F-35s, remained sitting on the tarmac.

Horse country

As the event ended, Hensoldt kept a close eye on any movement of the heavily guarded F-35s on the airfield. As exhibitors began to clear out, it looked like the chance of catching the planes during their inevitable departure back home would be lost.

But in Hensoldt’s telling, someone had the idea of setting up TwInvis outside the airport, which ended up being at a nearby horse farm.

Camped out amid equines, engineers got word from the Schönefeld tower about when the F-35s were slated to take off. Once the planes were airborne, the company says it started tracking them and collecting data, using signals from the planes’ ADS-B transponders to correlate the passive sensor readings.

A spokeswoman for the F-35 Joint Program Office said she was unable to comment by press time on Hensoldt’s claim of having tracked the aircraft in Berlin or about the plane’s general vulnerability to passive radar.

There are several horse and pony farms in the vicinity of Schönefeld Airport, offering everything from riding lessons to horse-themed summer camps for kids. A woman answering the phone at the business closest to the airfield, “Keidel Ranch,” a couple kilometers to the west, confirmed to Defense News that “someone” from the Berlin Air Show had showed up and stayed for “two or three days.”

Hensoldt previously said its passive-radar detection works regardless of whether the targeted aircraft has radar reflectors (so-called Luneburg lenses) installed. Those features — little knobs on the roots of the F-35 wings — can be seen in photos released by the U.S. Defense Department on the occasion of the journey to Berlin.

The reflectors are often mounted on the stealthy aircraft to make them visible to local air traffic authorities during friendly missions, like air show appearances. They artificially create a radar cross section in the frequency bands in which airspace-deconfliction radars operate so that traditional, defense radar systems know what they are dealing with.

According to a source close to the program, Luneburg lenses mounted on the departing F-35s would make it a certainty that the jets can be tracked, suggesting that the situation would be different without the reflectors installed.

“When the F-35 is not flying operational missions that require stealth — for example, at air shows, ferry flights or training — they ensure air traffic controllers and others are able to track their flight to manage air space safety,” Lockheed spokesman Michael Friedman wrote in a statement to Defense News. “The Air Force can best address questions related to their F-35s participation at the Berlin Air Show.”

Hensoldt argues that passive-radar detection works in a different spectrum, making the presence (or absence) of reflectors irrelevant. In layman’s terms, passive radar tracks the entire physical shape of planes, versus being triggered by smaller, angular features on the body of a jet.

Talking stealth

Whatever Hensoldt's claims, the German military has embraced passive radar as an emerging technology key for future capabilities, including air defense. Earlier this year, the country's Air Force was in the process of creating a formal acquisition track for passive sensing, Defense News reported.

That step came after the Defence Ministry sponsored a weeklong “measuring campaign” in southern Germany last fall aimed at visualizing the entire region’s air traffic through TwInvis.

Also noteworthy, in the year and a half that followed the air show, emphasis on stealth features for the Franco-German-Spanish Future Combat Air System program, meant to be Europe's next-generation warplane, shifted.

Officials from the industry teams involved in the program increasingly converged around the idea that stealth as we know it had lost its shine — this following rumors circling the German defense scene about how Hensoldt had apparently managed to light up the American aircraft on the radar screen.

Valerie Insinna in Washington contributed to this report.

Sebastian Sprenger is associate editor for Europe at Defense News, reporting on the state of the defense market in the region, and on U.S.-Europe cooperation and multi-national investments in defense and global security. Previously he served as managing editor for Defense News. He is based in Cologne, Germany.