Top national security leaders have been warning that the world is becoming an increasingly dynamic place in which everyone from friendly forces to adversarial nation states, terrorist groups and criminal organizations have unprecedented access to the same commercial technology.

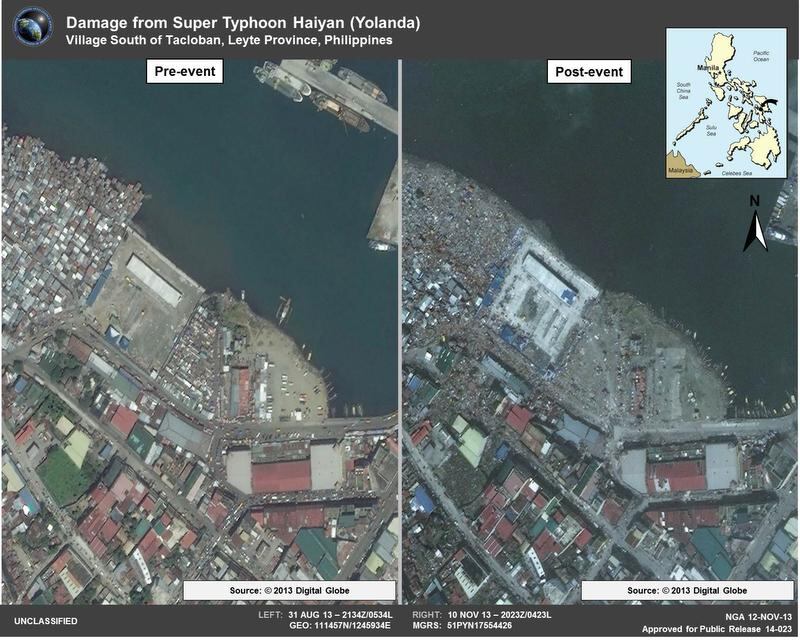

This new dynamic world — one in which the truth can be much more easily fabricated — is posing problems for intelligence agencies that seek to provide policy makers with answers to questions and context surrounding world events.

“Facts are not what they used to be,” National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency Director Robert Cardillo said during a keynote speech April 23 at the annual GEOINT symposium in Tampa, Florida. “What’s real, what’s artificial, what’s fabricated and how do we know. In such a world, that’s less tethered to ground truth, one grasps for context and coherence.”

NGA will be releasing a new updated strategy soon, and while Cardillo told reporters at the symposium that the strategy will be mostly fine-tuning, one area of elevation from when the current strategy, now three years old, will be greater focus on adversaries’ capabilities.

RELATED

“We have [to] … ensure that GEOINT is competitive with and can defeat in the race the adversary’s capability,” he said. “I probably was not as clear in [2015] because it wasn’t clear in my head about the nature of the adversarial use of common geospatial applications.”

One example Cardillo provided was the 2014 shoot down of a Malaysian passenger jet over Ukraine, attributed to Russian-backed separatists.

While there was debate and fact-finding efforts at the highest levels among western nations of who was responsible for the shoot down the Russians had two or three or four narratives out, Cardillo said.

“It was the Ukrainian military, it was a rouge operator who had stolen a piece of Russian equipment, it was a Ukrainian fighter plane,” he said of the Russian narratives. “There were three or four, you can’t even call them counter-narratives because they didn’t even have a central narrative yet. That’s my point.”

This was a great example, he added, of how adversaries can create confusion within the international community using something as simple as a doctored image.

“That was five years ago, it was done with Adobe photoshop. It was pretty simplistic. The world’s gotten a lot better. I don’t know that it will be as obvious next time,” he said. “Somebody has a picture that looks really authentic that supports your counter-narrative, boy that’s confusing.”

Cardillo said there is already similar counter-narratives occurring in Syria following the multilateral April 13 strikes against alleged chemical weapons factories.

While these practices are hardly new, Cardillo expressed that with the advancements in technology today “people are going to get a lot better at it and, let’s face it, in a world in which we tend to live in our own news cocoon, we know what we like … it’s really easy to reinforce somebody’s internal narrative with a doctored picture.”

Mark Pomerleau is a reporter for C4ISRNET, covering information warfare and cyberspace.