After a summer of what seemed like endless missile tests, North Korea stayed quiet for 75 days, before resuming on Tuesday. So did we see it coming? Notable movements are visible from space, but it takes human knowledge to figure it out, and without deep knowledge of the context, people can get it wrong.

Consider, for a moment, this example from Jeremy Hsu: “Satellite images of North Korean missile testing sites or nuclear reactor facilities can sometimes reveal smears of yellow or befuddling brown objects at certain times of the year. A casual armchair observer might suspect those patterns as indicating something nefarious. But they actually represent a mundane harvest practice — North Korean workers often dry out their corn harvest on pavement before putting the harvested crop into brown sacks.”

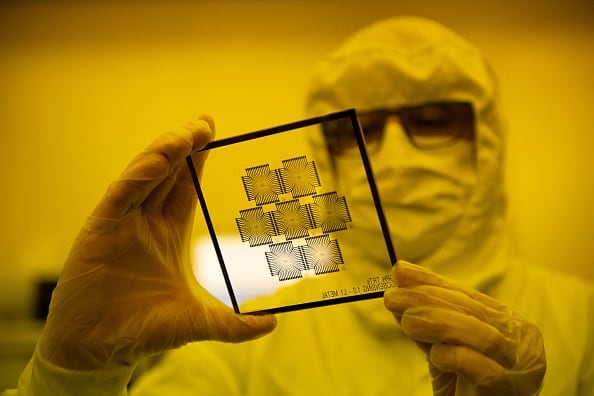

For the open source intelligence community, as well as the nonproliferation community, satellite footage is at least as much about observing what is visible, as it is deciphering human behavior. Outside the strict work of intelligence agencies, we’ve already seen how the World Bank used satellite imagery to figure out the oil revenue of ISIS.

Likewise, in the nonproliferation space, the International Atomic Energy Agency has used satellite imagery to keep an eye on the North Korean nuclear program from almost the beginning, using the bare truth of buildings seen from the heavens to track what happens, without requiring any personnel on the ground.

“Although [South Korea] has protested about the Agency’s reliance on such imagery,” wrote IAEA Director General Hans Blix in 1995, “it does not seem reasonable that the Agency should refrain from utilizing a type of information that is available to the whole world even commercially — and that has long been used for confidence building in the field of arms control.”

In 2014, a study by the Open Source Information for Nuclear Security project noted that using satellite imagery and other open source tools, researchers were able to identify both a potential ballistic missile transport vehicle checkout complex and potential gas centrifuge manufacturing related facilities in South Korea.

Now within hours of the release of new photographs, multiple researchers can publicly identify the same North Korean missile launch preparation site. Aided by open-source satellite imagery and with the pinpoint purchasing of commercial photos, we can know where, exactly, an engine of destruction was prepared once the range of locations is narrowed down.

And, sometimes they can find the grain harvested instead, during the harvest lull between missile seasons.

Kelsey Atherton blogs about military technology for C4ISRNET, Fifth Domain, Defense News, and Military Times. He previously wrote for Popular Science, and also created, solicited, and edited content for a group blog on political science fiction and international security.