About two years ago, James Clapper, then the U.S. director of national intelligence, officially added genome editing to a list of threats posed to national security. Clapper’s concern was with genomic editing research “conducted by countries with different regulatory or ethical standards than those of Western countries.”

But a new field of scientific inquiry says that the threat posed by biotechnology presents an entirely unrealized area of vulnerabilities that has thus far received little public attention.

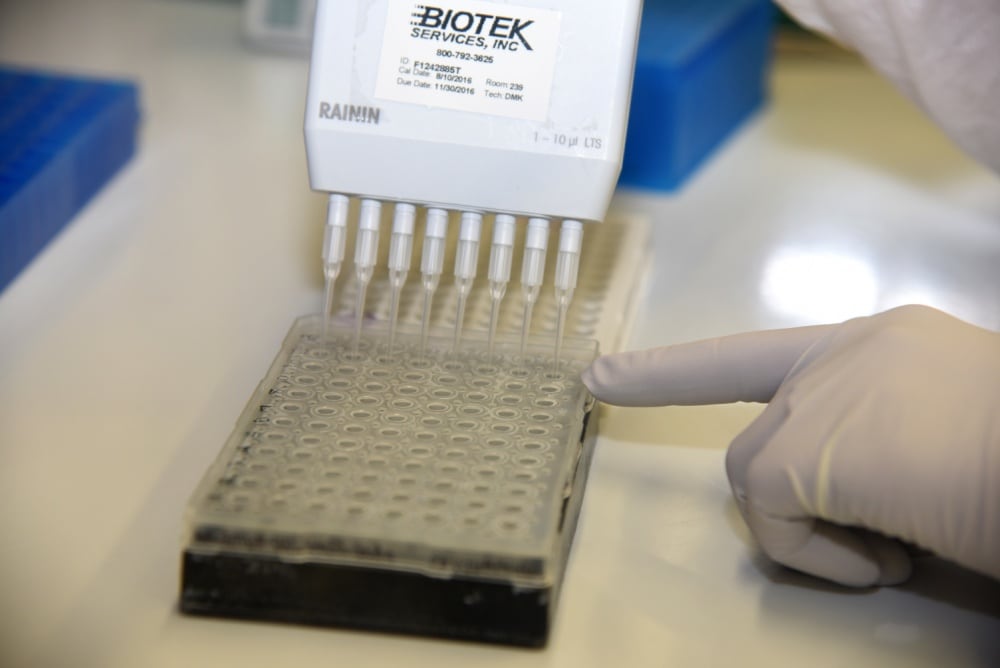

Cyberbiosecurity, an emerging research field, posits that the biotechnology industry’s and other life science and medical fields’ increased reliance on computer-controlled instruments and networks is leaving biological data, critical instrumentation and facility operations vulnerable to cyber-based attacks. Researchers in the new cyberbiosecurity field are exploring the enormous range of threats posed by such attacks and how to defend against them.

“Imagine if our adversaries had access to the health records or personal genomic data of all of our deployed forces around the world,” said Randall Murch, a professor at Virginia Tech, who recently led a specific systems analysis project to study cyberbiosecurity for the Department of Defense.

“They could understand what our biomedical or genomic strengths and weaknesses are and potentially weaponize to that advantage.”

Traditionally, there have been two separate approaches to security within the biotech community: biosafety and biosecurity.

Biosafety policies are designed to prevent unintentional exposure to pathogens or accidental release of biological agents, while biosecurity focuses on preventing illegal spreading of hazardous agents, typically by bioterrorists. Neither of these, according to cyberbiosecurity advocates, address the threats resulting from the increasingly intricate relationships between computers and biotechnological experiments and the infrastructures that support these.

This kind of relationship was on full display in August 2017, when a team of researchers at the University of Washington used DNA to take over a computer system. To do this, the scientists coded strands of DNA with malware that read as 0s and 1s, the language used by computers. When those strands were sequenced, the malware was activated, allowing the scientists to take over the computer analyzing the DNA. While in this case DNA was used to maliciously attack software, it’s easy to imagine how DNA sequence data merely stored on a computer could be hacked and weaponized against the physical world, or misused in other ways.

In 2006, in an effort to show how easily terrorists could access biological weapons, a Guardian journalist successfully obtained a short sequence of smallpox DNA from a public online database. Thanks to computers, editing a DNA sequence is nearly as simple as coding a computer file, and it can be done with malicious intent.

Cyberbiosecurity advocates are working with the U.S. government to demonstrate how this emerging threat could affect national security. The Department of Defense recently funded a $750,000 project to assess the security of biotechnology infrastructures. The results are for official use only, but the researchers explored part of their findings in a research paper titled, “Cyberbiosecurity: From Naïve Trust to Risk Awareness.” Some researchers involved in that study would like to see the government do more.

“If the Department of Defense thinks they’re impervious to cyberpenetration of this kind, they might want to think again,” Murch said.

“Even if the problem hasn’t happened yet, it could. It’s time to get out ahead of it. A comprehensive, lean-forward perspective is warranted.“

Despite the clear risks biotechnology presents, researchers say there is an alarming level of naivete among those closest to the data behind the technology. Along with new policies to address these growing risks, cyberbiosecurity researchers say a first step in improving cyberbiosecurity comes with the culture.

“Biologists need to develop a culture of security in their labs,” said Jean Peccoud, Abell Chair in synthetic biology at Colorado State University, to InnovatorsMag. “Most of us are incredibly naïve when we walk into our labs.”