One of the keys behind major pushes within the Pentagon to develop new technologies are advancements by so-called near-peer competitors. Chief among them: Russia.

In the assessments by several top military leaders, Russia poses the greatest strategic threat to the U.S. and its allies. Russia's capabilities in cyber, unmanned systems, special forces (sometimes referred to as "little green men"), proxies – all taken together as so-called hybrid warfare – have forced the U.S. to reassess how it fights and organizes.

The new push toward multi-domain battle, which involves seamless coordination and operations across the five domains of warfare, as well as the third offset strategy are being undertaken in large part from observations of Russia's capabilities.

"We did this Russian New Generation Warfare study. That’s what essentially spotlighted for us that there were old technologies being used in new ways and new technologies being used in new ways, and the combination of those are creating gaps that we do not have solutions for," Maj. Gen. Bo Dyess, acting director Army Capabilities Integration Center at the Army’s Training and Doctrine Command, told reporters during AUSA Global Force Symposium in Huntsville, Alabama, in March. The study was commissioned in February 2016 and the author traveled to Ukraine to see what Russia was doing in Ukraine.

So what does Russia's capabilities look like and how do they stack up against the U.S.?

"I think if you look at their force, from what we know as hybrid or asymmetric means to conventional to nuclear, they are modernizing," in every one of those categories, Gen. Curtis Scaparrotti, commander of European Command, told the House Armed Services Committee during a March 28 hearing regarding Russia’s capabilities.

Peter Zwack, senior Russia-Eurasia fellow at the Institute of National Strategic Studies at the National Defense University and a retired Army brigadier general who served as the attaché to the Russian Federation, noted that since at least 2014, the West has gotten a glimpse of Russia’s full-spectrum operations. Those capabilities range from gray zone conflict to strategic level operations in Syria.

Scaparrotti added that within the hybrid context, Russia’s use of cyber is well known, as well as their use of disinformation or "information confrontation" as the Russians call it. Unlike the U.S., Scaparrotti continued, Russia views these activities below what the U.S. calls the threshold of conflict to include political provocation, information operations, disinformation, cyber and related activities. This is now a functional part of Russia’s doctrine, he said.

Given the range of sectors these types of hybrid operations cross – military, civilian, government, private sector – Scaparrotti noted the need for a whole of government approach to combat Russia’s activities because to be successful, it is imperative to combat Russia in all the areas they are operating.

From the military context, a specific example of Russia’s cyber capabilities as it applies to battlefield operations was identified in a reportreleased at the end of 2016 by the firm CrowdStrike. The report outlined an implant distributed by a Russian military intelligence unit known as the GRU within Ukrainian military forums that was eventually loaded to Android mobile devices. It was then used by the Ukrainian military to more quickly processes targeting data. The implant allowed Russians to surveil Ukrainian soldiers and access their location – a similar capability U.S. cyber operators have sought.

Martin Libicki, a visiting professor at the U.S. Naval Academy’s Center for Cybersecurity Studies, noted in a recent essay publishedin the Air Force's Strategy Studies Quarterly that Russia and others are converging information warfare in theory and in practice in areas like Ukraine, featuring "an admixture of specialized units (speznats and artillery), logistical support of local insurgents—and copious amounts of IW."

Libicki added that Russia’s tactics also include distributed denial of service attacks on Ukrainian websites, cyber attacks on their power grid, electronic warfare and "near-successful attempts to corrupt Ukrainian election reporting."

"Russian cyber espionage against Western targets appears to have grown; they are certainly being detected more often," he wrote. "Examples include NATO and the unclassified e-mail systems of the White House, the U.S. State Department, the Joint Chiefs of Staff, the Democratic National Committee, and the German Parliament."

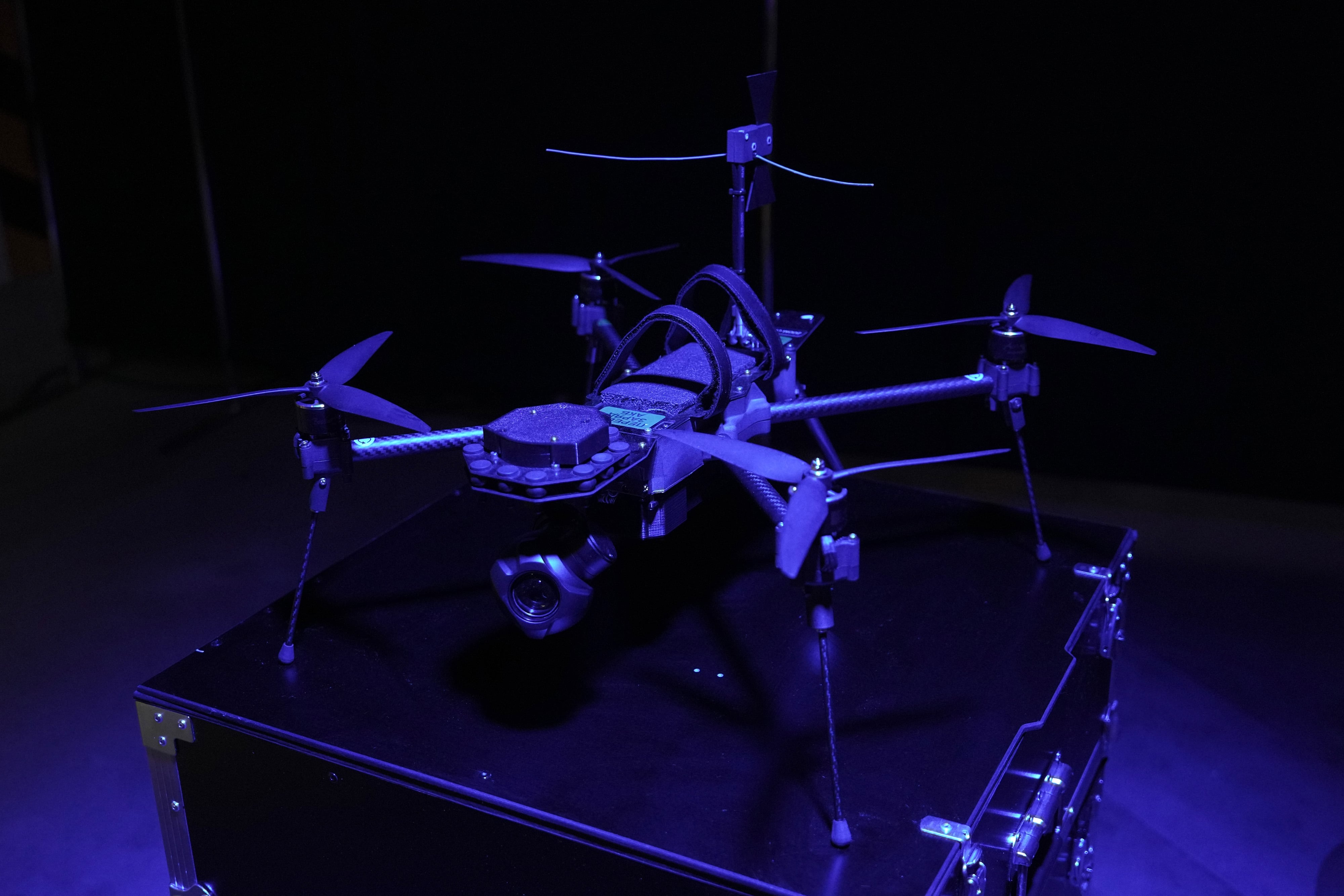

Russia has demonstrated advanced jamming and electronic warfare capabilitiesin Ukraine, even disrupting the control links between the drones of international conflict monitors. As far as their own UAV operations, Russia has made significant improvements from years past.

"Russian UAVs are able to fly overhead and spy on formations, [which is something] that we haven’t had to worry about for the past 15 years. And then they’ve got precision fires that are connected to their UAVs," Lt. Gen. Ben Hodges, commanding general of U.S. Army Europe, saidin August.

Scaparrotti also called for continued investment in anti-submarine warfare, noting that while the U.S. is still dominant in this domain, continued investment is necessary to keep deterring and remaining dominant as Russia has made significant advancements in the undersea domain, he said.

In Ukraine, Scaparotti explained that the Ukrainian military is fighting a "lethal, tough enemy; it’s a Russian proxy, really," adding that Russia provides these proxies and their forces operating in Ukraine some of their newest technology to test, such as unmanned aerial vehicle sensor-to-shooter techniques.

Despite these clear advancements in capabilities, Zwack, the retired general, poured cold water on the notion that Russia might have the U.S.’s number. Given their manpower and a number of other factors, he said during an event hosted at the Atlantic Council in Washington March 28, the Russians will have a tough time generating a lot of combat power across all their borders at one time. That means they could probably do something very well in one area, but hold everywhere else; however, their military is built to get into something quickly.

"They understand the correlation forces better than anybody. They know in a stand-up conflict with us and our allies, it’s not going to go well for them – they have to get in fast," he added, noting this will include laying the ground work with disinformation, advanced electronic warfare, ISR, reconnaissance and command and control. "These things the Russians really improved" since 2014.

"The Russians focus on asymmetries – asymmetries is first a retaliation of one’s own vulnerabilities and the Russians know that," he said, For example, Western democracy, the rise of nationalism and free speech all have been exploited in recent influence operations.

Within the European theater, Scaparotti said that while the U.S. and its allies can do their job to deter threats from Russia and terrorism, given the evolving threat Russia and creativity terrorists present, the force must be relevant to those threats. One of the things Scaparotti said he needs to continue to deter is more intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance.

"To deter properly," he said, "I have to be able to have a good baseline of Russia in particular so that I know when things change I can posture my forces properly. I need increased ISR to have good indications and warnings to set that posture properly over time."

While declining to offer greater details, Scaparotti said he would offer members of the committee specifics regarding needed capabilities given the advancements of adversaries in the region.

In terms of Syria, Zwack said Syria was not that big of an operation as far as numbers for Russia, but "they moderated it, they modulated it, they put together a force package, they did their operational security very well" and they conducted a well-executed operation.

He also asserted that Syria will be a Russian enclave for a long time as they have their anti-access/arena denial umbrella there, a reference to anti-aircraft surface-to-air batteries keeping adversarial aircraft at bay.

Mark Pomerleau is a reporter for C4ISRNET, covering information warfare and cyberspace.