In deterrence, there are two choices: denial or harm. For the Defense Department, deterrence policy as it applies to space reflects the former.

"As we look at the dynamics of space, as we look at how space works and we try to figure out how are we going to deter adversaries from attacking space capabilities, we have two choices — because deterrence is always a two choice thing," Douglas Loverro, deputy assistant secretary of defense for space policy, said at an Oct. 14 breakfast hosted by the Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies.

Deterrence is either going to deny a benefit or inflict harm to hurt the adversary to make sure that their actions can't hurt you, he said.

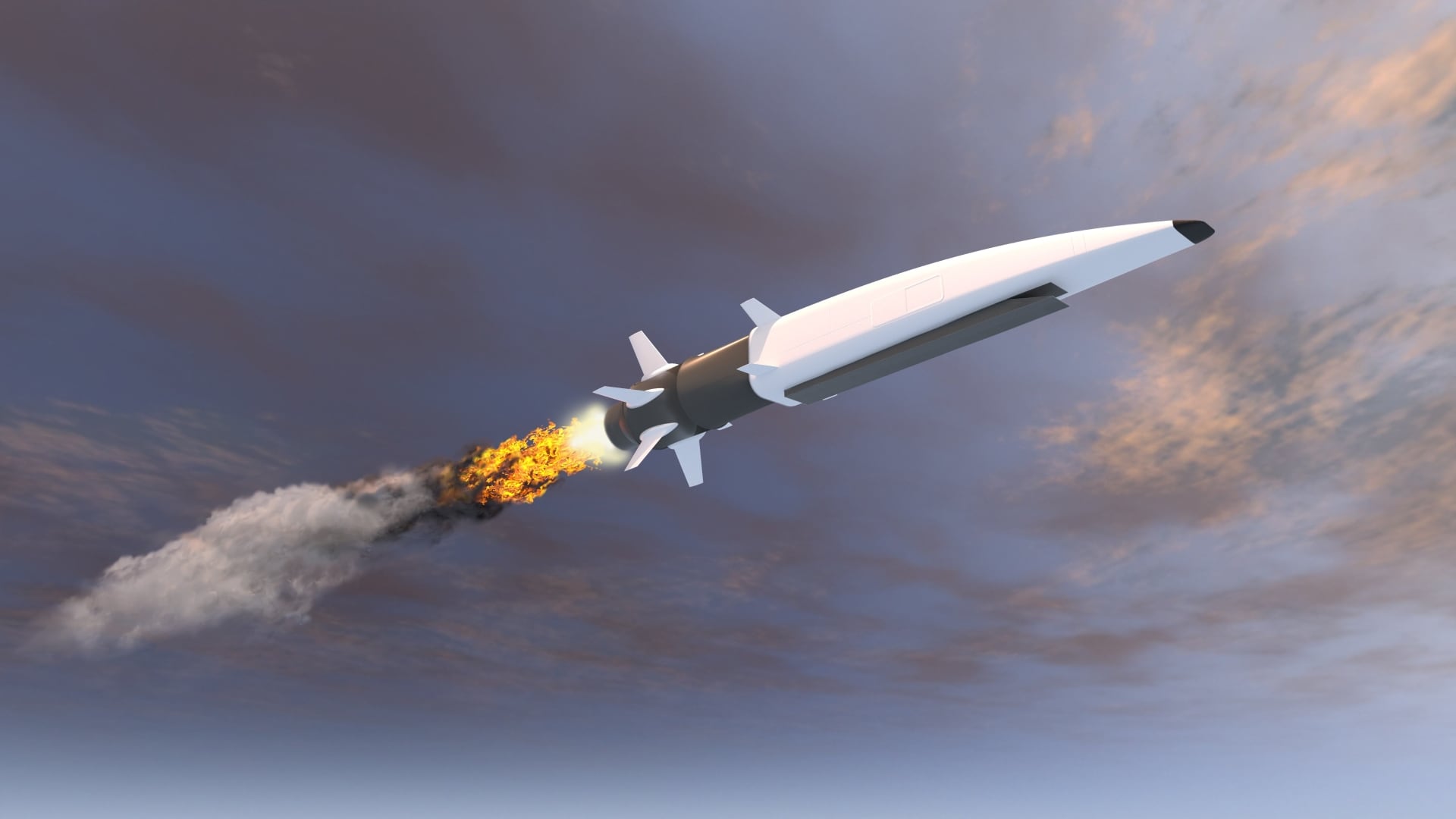

Regarding a deterrence policy aimed at the threat of force, Loverro said it would be difficult to deter others from attacking space assets by threatening to attack them back. He also said it could be difficult to justify an attack by the U.S. on another nation's territory when that nation attacks a satellite that the U.S. does not even admit exists.

So if one is reliant on a retaliatory strike for deterrence in space, Loverro said, that could be an "iffy" thing, noting that in a recent war game, officials were not even sure what an attack in space could look like: Is jamming an attack? Is a laser an attack? Does it have to be a kinetic effect and attack?

These issues aren't settled in international law and probably won't be for some time, he said.

Assurance is also a critical metric in a deterrence-by-denial strategy. The United States, Loverro said, has laid out levels of assurance, and it's rapidly defining architectures for systems to get to that level of assurance. He declined to offer additional details, noting that if he did these assets would be less assured.

Yet, this hits on the notion that if no one knows deterrent capabilities, what good are they?

Loverro said the U.S. must demonstrate some level of assurance for its space assets.

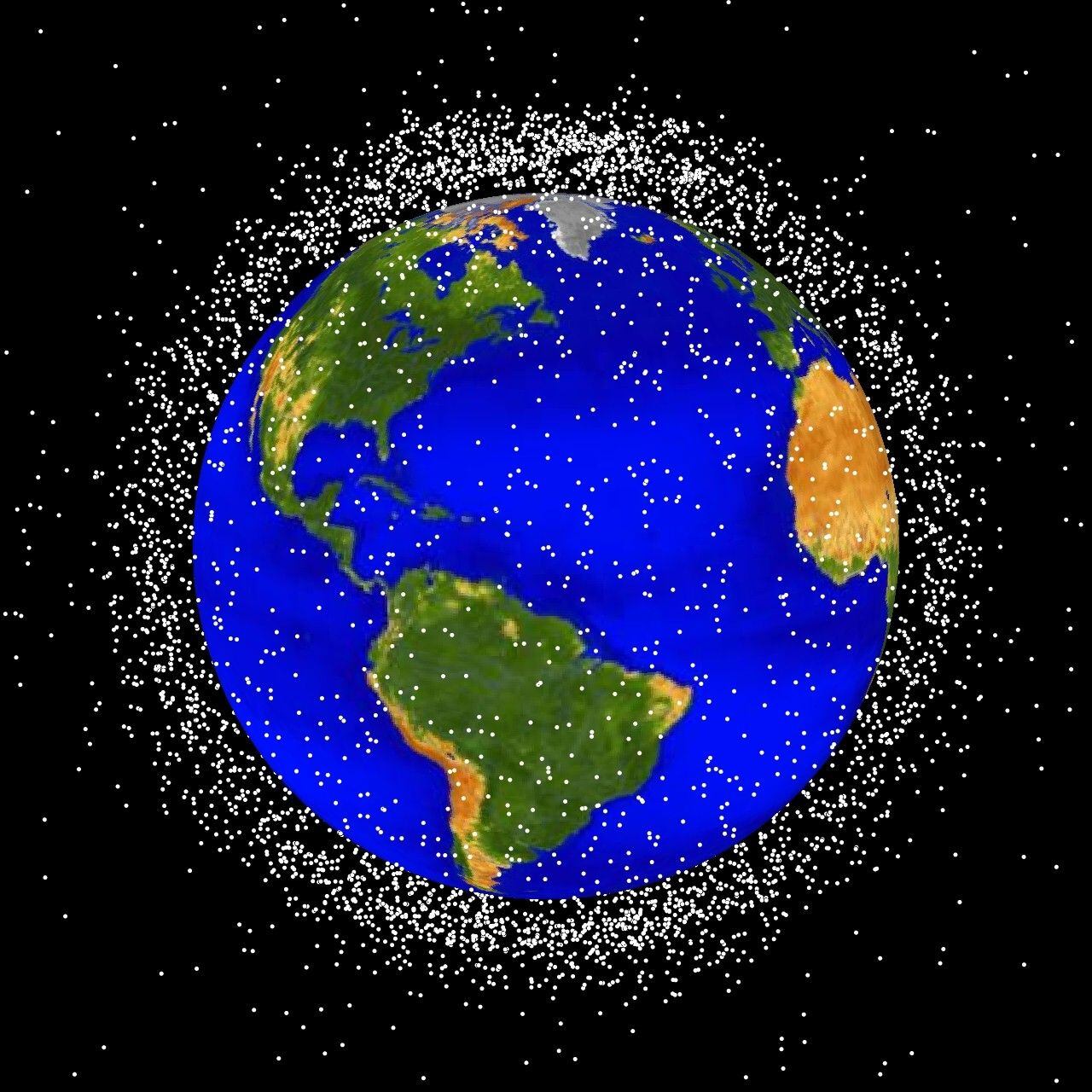

When assessing that a deterrence strategy to deny any benefit to an adversary would be more suitable, Loverro said the benefit of a potential attack on U.S. systems would have to be measured by adversaries. Would an attacker risk international condemnation for creating debris in space, referencing a 2007 event in which the Chinese conducted an anti-satellite missile test that caused a great amount of threatening debris? Will adversaries risk the ire of U.S. partners if they have to attack a French satellite in order to deny the U.S. the ability to image its territory, he again asked rhetorically.

Given the multitude of these issues, Loverro noted, it is the U.S. position that taking an approach of assurance and benefit denial in an attack — making it politically difficult to wage an attack — and perhaps utilizing economic sanctions or retaliatory actions at a lower level is a better way to deter attacks in space than completely depending on retaliatory strikes.

He also said it's unclear how a war, if it transitions to space, would evolve. What is clear, however, is that space communities are responsible for ensuring space capabilities for ground and terrestrial forces, because what really deters attacks on the U.S. is its ability to participate in the conflict via other domains, he said.

Mark Pomerleau is a reporter for C4ISRNET, covering information warfare and cyberspace.