WASHINGTON — The United Kingdom’s recent guiding plan for its military included both cuts to existing systems and investments in new technologies, with a special emphasis on increasing the U.K.’s capabilities in space.

During an April visit to Washington, Air Chief Marshal Mike Wigston, the head of the Royal Air Force, sat down with C4ISRNET to discuss some of those investments outlined in the Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

One item listed in the integrated review was a new intelligence surveillance and reconnaissance satellite constellation. Can you elaborate on what the thinking is there?

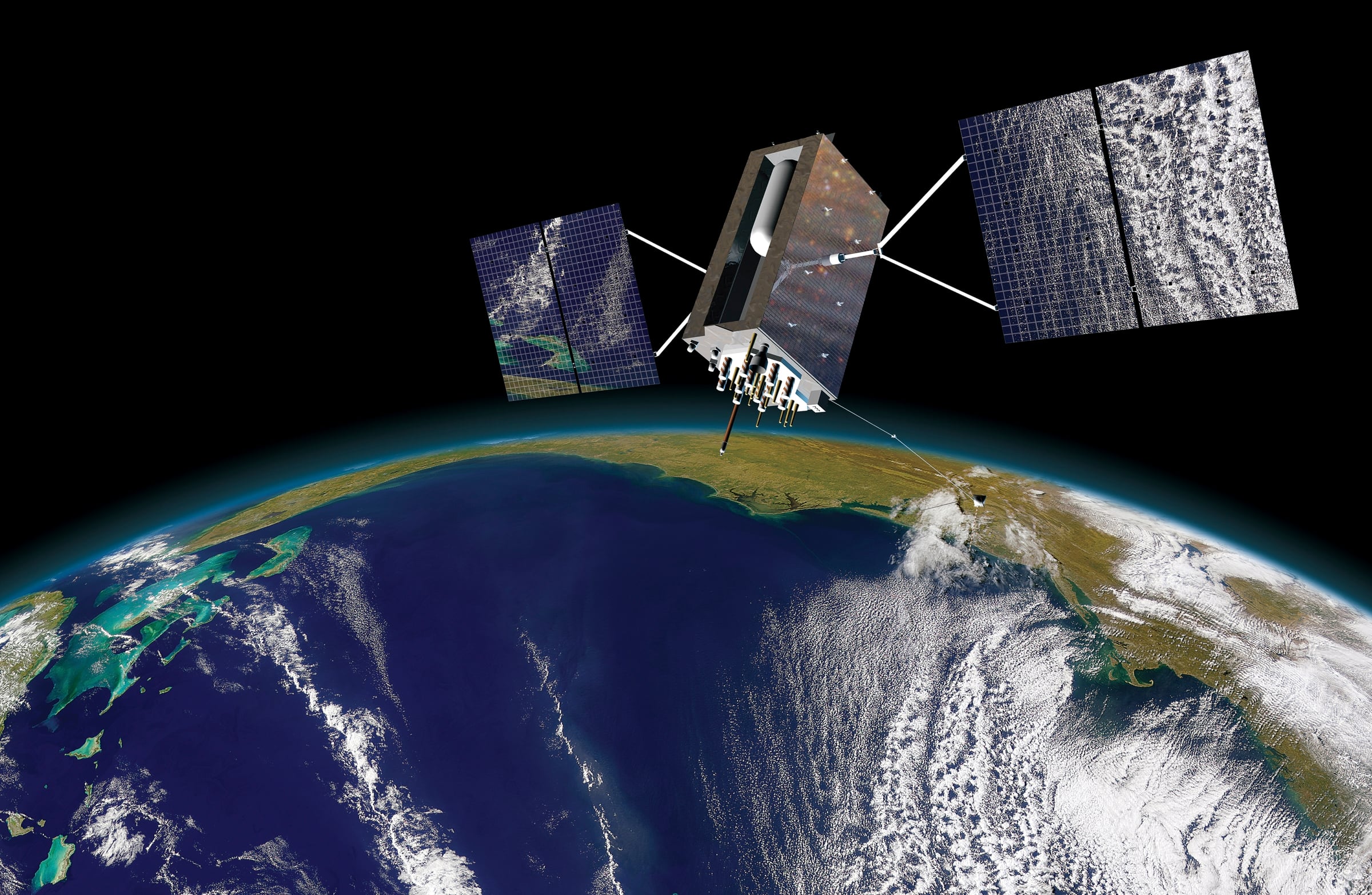

Our aim for that program is a [constellation of] responsive launched small satellites, low Earth orbit constellation, where we have the option of selecting the payloads, selecting the role and selecting the position of the satellites, and then launching them and getting them into operation in a very, very short decision action cycle. This is something that is attractive to me as an operational commander. And I think it will have direct utility for the war fighter, that ability to respond to a crisis in a particular part of the world, or perhaps a requirement to add some resilience to another part of the space network. [This design] means we can respond, launch and get something into service very rapidly. And that’s the work that we will be continuing over the next couple of years, for that particular aspect of our space program.

The U.K. government has invested in the company OneWeb. Is that something you think might be a fit for this system?

The U.K.’s investment with OneWeb was a another part of government, so that’s separate from the United Kingdom’s Ministry of Defence. But there are elements of OneWeb — and all of the similar systems that are being launched into space at the moment — around the command and control, the level of autonomy and autonomous control in those satellite constellations, where there’s huge numbers of small and very small satellites working together. So there are elements of what OneWeb is doing, which are of interest to me, in a similar way to some of the other similar systems that have been launched at the moment. But that’s not something that I’m directly involved with.

The U.K. was involved in the European navigation system known as Galileo but was forced out following Brexit. British official discussed doing a U.K.-only system, but that has been delayed and is seen by some analysts as too expensive. What is the current status of these discussions?

So again, the primary responsibility for that is in another part of government, but of course, the Ministry of Defence is involved because of our interest in, and the importance of, GPS and global positioning. And we’re still analyzing and assessing what the options are, because nobody needs us to build a direct duplication of a system that’s already in place like GPS. But what would be really helpful, as we look at a more challenged, a more competitive [space] and potentially a need for greater resilience in space, is a system that’s complimentary, that might be made in a different model, with a mix of nodes on the network, some of them on the surface of the Earth, some of them in space. There are some options there, and an opportunity to do something different, which is complimentary to GPS, but that adds resilience in a different way. So I’m very keen that we continue to explore that. And it’s certainly something that the U.K. has some world-leading technologies, and we’ve got a lot to offer. And so that will be something that we will continue to work on over the next few years.

The U.S. stood up both a Space Command and a Space Force in the last couple of years. The U.K. is now spinning up its own Space Command. Can you walk us through what that’s going to look like, and what the interaction with its U.S. counterpart might be going forward?

The U.K. Space Command is an opportunity for us to bring together some quite disparate elements — of largely Royal Air Force units — that are operating in space and are closely linked in with U.S. Space Command and the U.S. Space Force already, but we haven’t had a unifying command and control and a unifying organization for them. I think this, at the very outset of the U.K. Space Command, it’s an opportunity for us to bring together everything that we’re doing in space, in the Royal Air Force and in the U.K. Ministry of Defence, bring it all under one organization to make sure that we’re channeling the investment that we’re going to make, that we’re giving the people in that organization the skills and the equipment they need to make sure that we are living up to our ambition and our prime minister’s ambition for the U.K. to take a leading role in Europe in space. And so the Space Command will be that nodal point where we engage with allies, like the United States, that we share information, that we develop new systems, and that we continue to benefit from all of the opportunities that space offers.

Across the board, the commercial sector outspends governments on technology investment, but it’s particularly true with space. You have billions earmarked in the integrated review for space, which is real money, but the reality is that you will need to rely on private sector investment going forward. How do you make that work?

Space is already an enterprise where some of the leading progress that’s being made at the moment is in the commercial sector and private companies making enormous leaps in space technology and what we are doing in space. And so working closely with those will be a key part of the U.K.’s space plan and the U.K.’s role in space. The figures for commercial investment in space, of course they dwarf what we are doing from a military perspective, but our role is significantly different. Because whilst those commercial organizations are investing in space to provide services, to enable things to go faster and further on Earth to enable people’s day-to-day lives, the role of the Royal Air Force, the role of armed forces in space, is fundamentally different. We’re there to understand what some of our potential adversaries, some malign actors, are doing, to understand and to protect what’s our critical national infrastructure in space, and to be ready to defend it. That’s about information sharing, that’s about understanding and having a clear picture of what’s going on in space. And that’s about working with allies so that we’re ready to act when we see something which, you know, crosses the line of unacceptability.

Aaron Mehta was deputy editor and senior Pentagon correspondent for Defense News, covering policy, strategy and acquisition at the highest levels of the Defense Department and its international partners.