WASHINGTON — The first full year for the U.S. Space force marked an eventful stretch for the military in space.

From the growth of the nascent military branch to the award of massive new launch contracts, 2020 was a busy year in the space domain. Just this December, the Trump administration formalized its thinking about space in a new National Space Policy and gave Space Force members a surprise birthday gift: an official name. With new developments, launches and announcements spilling out throughout this year, even the most ardent observers could be forgiven for missing a story or two.

And so — without any more bloviating — here’s a recap of the top six military space stories of 2020.

The Space Force takes shape

While history will note 2019 as the year the Space Force was created, 2020 was the year the new service began to take shape.

Chief of Space Operations Gen. John “Jay” Raymond says his team had five focus areas for year one of setting up the first new branch of the military in 70 years: developing its people, developing its doctrine, presenting an independent budget, designing the force and presenting forces to a joint command. Raymond’s team has arguably made strides in all of those areas.

In 2020, the Space Force got its first member and chief of space operations, added 2,500 people to the new service, defined “spacepower” as distinct from military power in its capstone doctrine, set up the first of three commands, began implementing a series of acquisition reforms, and gave its personnel their official name: guardians. Questions remain, such as which capabilities and offices will transfer to the Space Force from the other services and what the new Space Systems Command will look like. Still, Raymond was optimistic about the progress made in year one.

“As I look back on this first year, I look back with great pride — great pride for the work that our space professionals have done in establishing this new service,” said Raymond in a December media call. “The progress we have made far surpasses anything I would have expected. We have completely reorganized the national security space organization — the largest restructure in our history.”

Space Development Agency orders first satellites

When the Trump administration created the Space Development Agency in March 2019, the office was a bit of an enigma. While most observers called for the consolidation of space systems acquisitions, the Trump administration established a new agency outside the purview of the U.S. Air Force. Furthermore, experts questioned whether the agency would survive the year, especially with the establishment of a Space Force imminent.

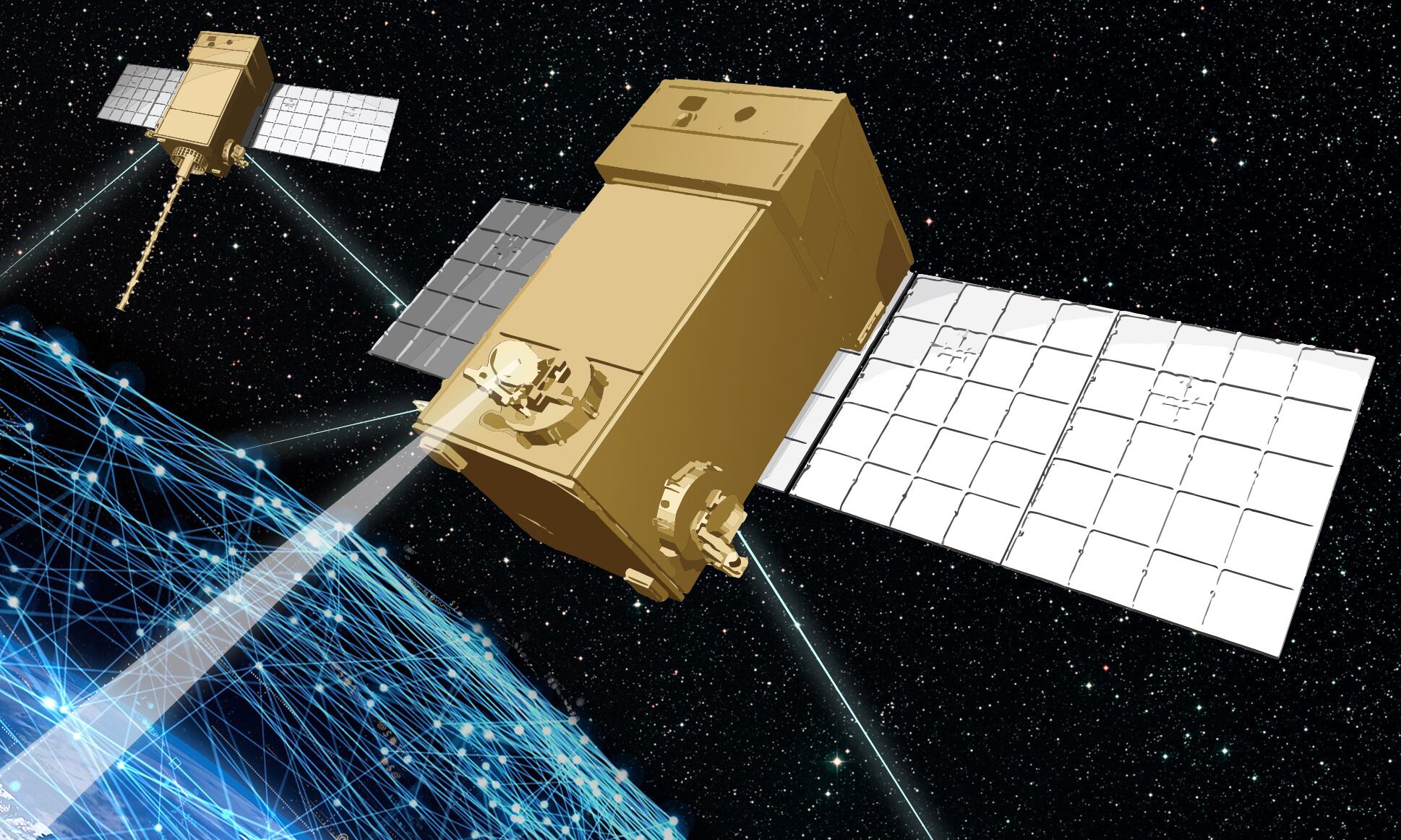

But in 2020, SDA defined its place in the nation’s space enterprise: building a new National Defense Space Architecture that will be made up of hundreds of satellites in low Earth orbit. The core of that architecture — a space-based mesh network — will serve as the space component of Combined Joint All-Domain Command and Control, the Pentagon’s effort to connect any sensor to any shooter across services and domains.

RELATED

And while the agency’s biggest advocate in the Pentagon — Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering Mike Griffin — left the government for the private sector, the office moved forward confidently in soliciting and awarding its first contracts over the summer. In August, the agency awarded York Space Systems $94 million and Lockheed Martin $188 million to build 10 satellites each for the inaugural transport layer. Then in October, the agency issued contracts for its first eight missile tracking satellites: $149 million for SpaceX and $193 million for L3Harris. A protest from Raytheon Technologies is holding up the tracking layer satellites, though SDA says it is taking corrective action and working to keep the effort on track for a 2022 delivery.

SpaceX and ULA win massive launch contracts

In one sense, the story of 2020 could be the emergence and success of several small launch providers despite a global pandemic. Yet the biggest launch contract of the year was for traditional heavy launches. In August, the Space Force issued its National Security Space Launch contract to SpaceX and United Launch Alliance, with the former receiving $316 million and the latter receiving $337 million.

The National Security Space Launch contracts will support more than 30 heavy lift launches for the Space Force and National Reconnaissance Office over a five-year period — from fiscal 2022 through 2027. Under the arrangement, 60 percent of launch services orders will go to ULA, with SpaceX taking up the remainder.

While the award is a major victory for SpaceX, which has fought tooth and nail to force its way into the lucrative military heavy lift launch market, it is undoubtedly frustrating for the two companies left out — Northrop Grumman and Blue Origin — which had been developing new rockets as part of the competition.

On-orbit servicing presents new opportunities

2020 marked the first successful docking of two commercial satellites on orbit as part of a commercial satellite life extension service offered by Northrop Grumman’s SpaceLogistics. That service involves attaching a SpaceLogistics Mission Extension Vehicle to an Intelsat communications satellite with depleted fuel reserves. By supplementing the satellite’s fuel reserves with its own and effectively towing the client around orbit, the MEV is expected to stretch the satellite’s service life by five years.

While the mission was entirely commercial, it has major implications for the military, which is looking into using SpaceLogistics’ services to extend the lives of its own satellites.

And commercial on-orbit satellite servicing could extend far beyond simply supplementing empty fuel reserves. Following the successful docking in February, SpaceLogistics announced a partnership with the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency on the Robotic Servicing of Geosynchronous Satellites (RSGS) program, which is working to create the first commercial spacecraft with a robotic arm that can perform repairs, augmentation, assembly, inspection or relocation of other spacecraft already on orbit.

SpaceLogistics is understandably bullish about the prospect of the military purchasing life extension services, and the Department of Defense has expressed interest. Other companies are eager to compete to provide those services. Most notably, Astroscale entered the field in June, providing its own slate of on-orbit servicing solutions.

Perhaps on-orbit servicing won’t be as feasible or cost effective as hoped, but 2020 was the year the concept became a reality.

Russia continues anti-satellite weapons testing

Throughout 2019 and 2020, the Pentagon used the development and testing of anti-satellite weapons by Russia and China as a justification for establishing the Space Force. And in 2020, Russia provided plenty of fodder for those who believe that nation’s space activities are provocative, to say the least.

In 2020, the Russian government conducted two tests of a direct-ascent anti-satellite missile, capable of taking out satellites in low Earth orbit. While Russia has tested such missiles in the past, pushback from the newly established U.S. Space Command brought the issue to the fore in 2020. The 11th combatant command was quick and direct in calling out the tests, which it characterized as aggressive.

“Russia’s DA-ASAT test provides yet another example that the threats to U.S. and allied space systems are real, serious and growing,” said Raymond, then-head of U.S. Space Command, after the first test in April. “The United States is ready and committed to deterring aggression and defending the nation, our allies and U.S. interests from hostile acts in space.”

The command continued its criticisms of Russia in December, when that government conducted another test.

“Russia has made space a war-fighting domain by testing space-based and ground-based weapons intended to target and destroy satellites. This fact is inconsistent with Moscow’s public claims that Russia seeks to prevent conflict in space,” Space Command head Gen. James Dickinson said. “Space is critical to all nations. It is a shared interest to create the conditions for a safe, stable and operationally sustainable space environment.”

But perhaps more concerning than the direct-ascent missiles was what USSPACECOM characterized as the testing of an on-orbit anti-satellite weapon. In July, USSPACECOM announced that a Russian satellite appeared to have launched a high-speed projectile into space, an action inconsistent with its stated purpose. A similar test was carried out in 2017.

U.S. officials have not shied away from characterizing this capability as a weapon — especially since Russian government satellites have a habit of sidling up to U.S. commercial and government satellites.

“China and Russia are continuing to develop space weaponry,” said Vice President Mike Pence in December remarks to the National Space Council. “Russia demonstrated a space-based anti-satellite weapon earlier this year. China is developing a new manned space station, and its robotic spacecraft will return samples from the moon in just a matter of weeks.”

Army tests space-enabled sensor-to-shooter pipeline

Superficially, the Army doesn’t scream space. Yet in 2020, the Army made big advances during Project Convergence that show how it plans to use new space-based capabilities to enable beyond-line-of-sight targeting.

Project Convergence is the Army’s new campaign of learning, an effort to transform the battlefield with artificial intelligence, developmental networks and new sensing capabilities. In short, the Army wants to be able to connect any sensor to the best shooter. Satellites were used both as sensors to detect threats and as a network to connect sensors and shooters across the battlefield.

Tactical imagery satellites were a major part of Project Convergence. Taking images of the battlefield from their high vantage point, a satellite would downlink its data to a TITAN surrogate, where artificial intelligence was then used to process that imagery, automatically detect threats, and provide targeting data to Army shooters. In this new setup, satellites can provide the essential sensing capability to enable beyond-line-of-sight targeting.

The Army also tapped into new commercial satellite networks in low Earth orbit to connect its systems. Using proliferated constellations such as SpaceX’s Starlink, the Army was able to transport data hundreds of miles in just seconds. Army officials say they will be able to experiment with even more capacity at Project Convergence 2021, as the commercial constellations become more mature.

All told, those space-based capabilities helped cut down the sensor-to-shooter timeline from 20 minutes to 20 seconds.

“I can tell you with confidence, there isn’t a person in the Army now who doesn’t understand or isn’t able to appreciate the capability that this deep sensing capability from space provides now,” Willie Nelson, director of Army Futures Command’s Assured Positioning, Navigation and Timing Cross-Functional Team, told C4ISRNET following the exercise. “There’s not a dry eye in the room when you look at how fast we can rapidly find threats and get those to shooters.”

Much, much more to come

Missing your favorite military space development of 2020? Perhaps you were more interested in the relaunch of the secretive X-37B space plane, the operational acceptance of M-Code Early Use, or even the completion of the Advanced Extremely High Frequency communications constellation. 2020 was a busy year to be sure, and 2021 looks to be equally enthralling as we learn about the Biden team’s plans for the space domain, see how the Space Force organizes its acquisitions, and find out how the military will utilize emerging commercial space capabilities.

Nathan Strout covers space, unmanned and intelligence systems for C4ISRNET.