UPDATE 9:00 p.m. —The Air Force’s 18th Space Control Squadron confirms the two satellites did not collide.

UPDATE 8:20 p.m. —Analytics Graphics, Inc. says early indications suggest there was no collision.

A nearly 40-year-old telescope and a 53-year-old experimental Air Force satellite are at a higher risk of crashing into each other tonight, with one satellite debris tracker putting the chances of a collision at 1 in 20.

Such accidents occur about once every five to nine years, according to the Inter-Agency Space Debris Coordination Committee, a group of space agencies from around the world.

The two long since decommissioned spacecraft are expected pass by each other —or possibly collide — at a speed of 14.7 km/s at 11:39 UTC Jan. 29. If they do collide, such an event would increase the amount of space debris on orbit, which poses a threat to active satellites, including those operated by the military and intelligence community.

“Close approaches like this do happen daily, it’s just a matter of this particular one appears to be unusually close,” said Ted Muelhaupt, principal director of the Aerospace Corporation’s southwest regional office .

Frequent conjunctions are generally on the kilometer scale. On Jan. 29, the two satellites are expected to pass within just meters of each other.

“For most of the close approaches that occur day, the probability of a collision might be one in a million or one in a hundred thousand or something like that,” said Roger Thompson, a senior engineering specialist. “If it’s an active satellite, generally the operators of that satellite start paying attention at around one in a hundred thousand.”

The first object is an experimental satellite launched by the Air Force in 1967. According to NASA, the Gravity Gradient Stabilization Experiment (GGSE) satellite helped inform the designs of Navy reconnaissance satellites launched in the 1970s.

RELATED

The second object is the Infrared Astronomical Satellite (IRAS). Launched in 1983 as a joint effort between the United States, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom, the telescope was used to take infrared imagery of the night sky during its brief 10 month mission. With any fuel long spent, neither satellite is capable of maneuvering today. Both objects are in low earth orbit.

The likelihood of a collision between the two long defunct spacecraft has fluctuated wildly over the past 48 hours as LeoLabs, a space debris tracking company, has learned more about the spacecraft and its orbit. On Jan. 28, LeoLabs lowered its projection, claiming there was now a 1 in 1,000 chance the two would collide. On Jan. 29., the company revised its estimates back to its original prediction: a 1 in 100 chance.

Then company officials discovered the boom. Apparently, GGSE 4 has a previously undisclosed 18-meter boom, and it’s not clear which way it’s facing. That greatly increases the likelihood of a collision. As of publication, LeoLabs predicts a 1 in 20 chance of a collision.

Part of the reason for the fluctuating chances is the inherent uncertainty involved with tracking objects in space, said Bob Hall, the technical director for space situational awareness at Analytical Graphics, Inc., a space situational awareness company.

“In essence, most satellites and pretty much all pieces of debris don’t have a GPS system on board,” Hall said. “So what happens is we use a variety of tools to track these things and with the measurements or tracts you get, you then have to use an orbit determination algorithm that processes those tracts and turns it into an orbit. There is an inherent uncertainty in that solution,” he added.

Uncertainty can be introduced through the minute bias’ of individual radars, the models determining gravitational effects, and even how the atmosphere creates drag on the satellites, whose orientations are unknown.

“Usually in low earth orbit, we’ll go about five-ish days (out), and much beyond that the error growth in the solution is too large to be practical,” said Hall. “You don’t want to really go too far in the future because there are so many uncertainties.”

RELATED

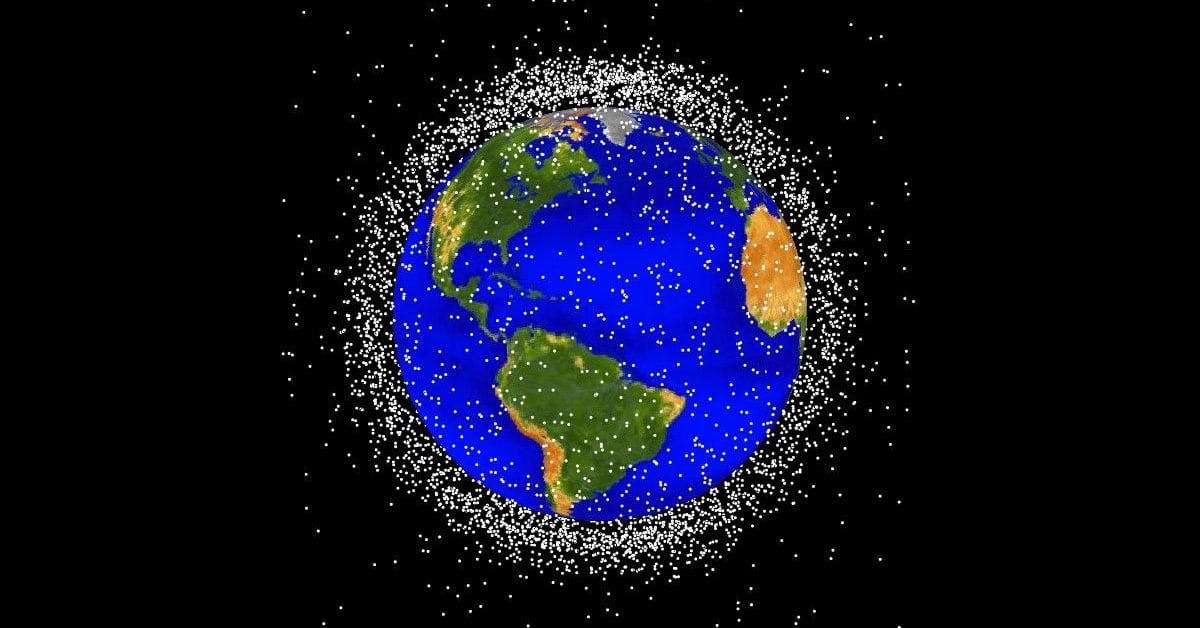

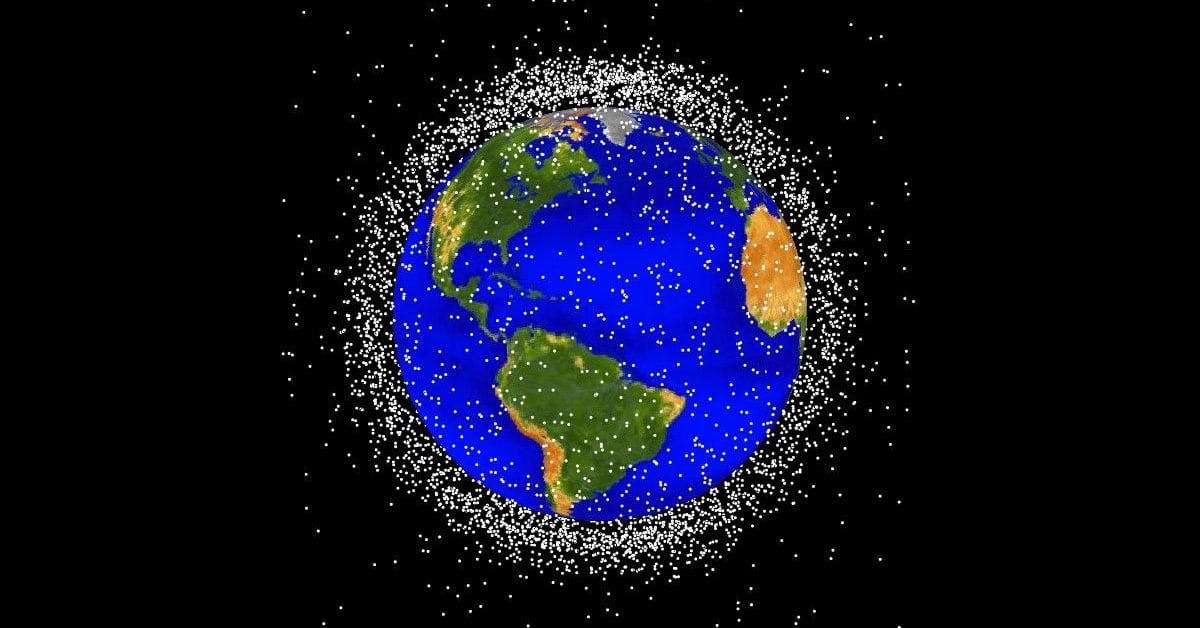

This could be the first significant collision between two satellites since 2009, when a decommissioned Russian satellite collided with an Iridium commercial communications satellite. According to the Secure World Foundation, the 2009 collision resulted in more than 2,000 pieces of space debris in LEO—and that’s just the debris that can be tracked. Smaller debris that can’t be tracked by current methods can also pose a threat to existing satellites. Anti-satellite weapons testing by China and India have also created new space debris.

The debris created by such collisions poses a major threat to the safety of the approximately 2,000 active satellites currently on orbit. Collisions can create thousands of pieces of new debris travelling at extremely fast speeds, each of which can rip through a satellite like a bullet.

“This is more of an example of how we should have done better debris mitigation in the past,” said Thompson. “It’s at 900 kilometers now, which is high enough that if it doesn’t collide, it could stay up there for over 100 years, almost 200 years, before atmosphere drag would pull it down.”

And assuming the launch rate of new satellites remains constant (which it hasn’t), similar collisions can be expected every five to nine years, according to the Inter-Agency Space Debris Coordination Committee.

“It is just a matter of time before one of these close conjunctions actually pays off. Think of this like lottery tickets—on the average a conjunction has a one in a million chance. But you buy enough lottery tickets and one of them is going to turn up,” said Muelhaupt. “We’re just waiting to see when that happens.”

The potential collision point is 900 kilometers directly above Pittsburgh, and it might be visible to the naked eye. Hall said at least one of the objects is visible to the naked eye and viewers might see a small change if there is a collision.

“It’s possible — it wouldn’t be like an orange explosion or anything,” he said. “You might see a change. You might see a temporary brightness change.”

AGI has a free app called Satellite AR that allows users to find on orbit satellites with their smartphones. According to the company, users could track one of the objects in question in order to figure out where to look to view the collision.

UPDATED 5:47 p.m.--This story has been updated with comments from space situational awareness experts from the Aerospace Corporation.

Nathan Strout covers space, unmanned and intelligence systems for C4ISRNET.