Northrop Grumman is on the verge of launching a new satellite-servicing vehicle that could extend the life of satellites by years, and the Pentagon is interested in becoming a customer.

The life span of a satellite is often limited by its allotment of fuel, which it uses to remain in its assigned orbit or to move to a new one. While a satellite might remain fully operational for years to come, if it runs out of fuel, then it’s the end of the road. So even though the technology already on orbit is still useful to a client, a satellite provider has to launch an entirely new space vehicle with enough fuel to replace the doomed satellite.

But what if satellites could be refueled on orbit?

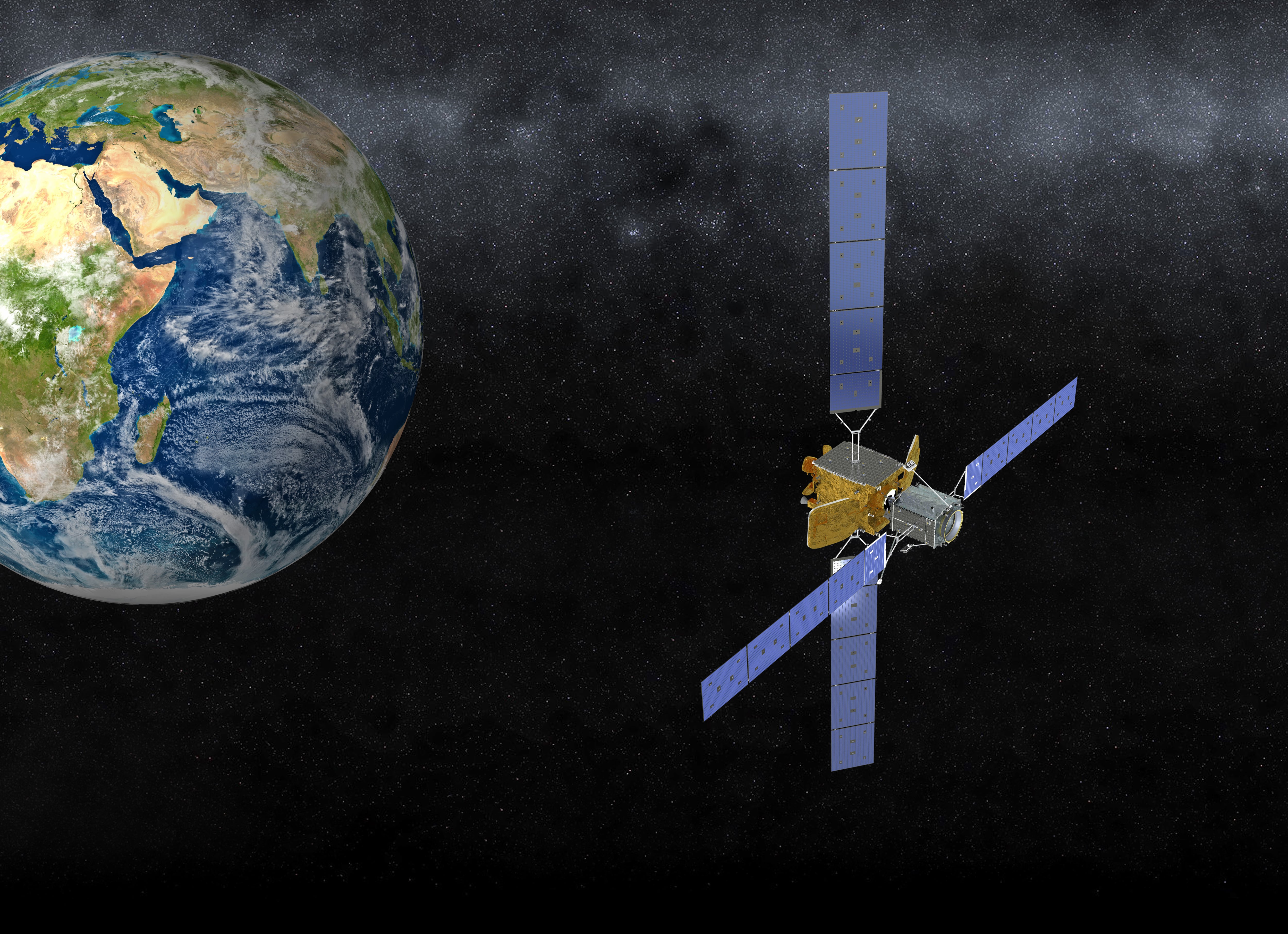

At the 2019 Global Satellite Servicing Forum on Oct. 1, leaders from SpaceLogistics, a wholly owned subsidiary of Northrop Grumman, said it’s on the verge of doing just that. Starting with the imminent launch of its first Mission Extension Vehicle, or MEV, the company is launching a satellite-servicing solution that can can extend a satellite’s life span by years by docking with on-orbit satellites and augmenting their propulsion.

While the launch of MEV-1 was delayed from Sept. 30, SpaceLogistics leaders expect their initial satellite-servicing vehicle will launch in the coming weeks.

The first client satellite is Intelsat 901, a communications satellite, said Joe Anderson, vice president of operations and business development for SpaceLogistics.

Following the launch, it will take MEV-1 about three months to meet up with Intelsat 901 in geostationary orbit. At that point, the Intelsat satellite will propel itself upward into the geosynchronous graveyard — an area above geosynchronous orbit typically used to dispose of satellites to prevent them from becoming orbital space debris.

From there, the space vehicle will approach the satellite and capture the client satellite.

Once attached, the mission extension vehicle takes control of Intelsat 901 using its electric propulsion to return the satellite to its geostationary orbit. The vehicle will remain docked for the next five years, extending Intelsat 901’s service life, before eventually taking it out to the geosynchronous graveyard for disposal.

Since MEV-1 has a 15-year design life, it can extend Intelsat 901’s service life longer, or move onto another satellite to provide the same service. It’s unclear exactly how much extra life this approach will provide to the serviced satellite.

According to Anderson, SpaceLogistics will be the first to market with its new on-orbit servicing solution.

And the Pentagon is interested in this technology. The Space Enterprise Consortium issued a contract to SpaceLogistics via the Air Force’s Space and Missile Systems Center in late July to study the servicing of four national security satellites in space. The deal is a four-phase contract, explained Joshua Davis, a member of the developmental planning and projects team at the Aerospace Corporation, a federally funded nonprofit that advises the Department of Defense. According to Davis, that contract is currently in a feasibility study phase, which will be followed by a deep technical dive, mission-unique hardware development and, eventually, the execution of a servicing contract.

“We are not buying a servicer, we are procuring commercial services,” Davis said.

He noted that SMC needs to focus on building serviceability into satellites now so that it will be easier to have each satellite’s lives extended once on orbit. The cost of design elements that would make government satellites easily serviceable is negligible, said Davis, and it can save millions of dollars down the line.

Although Davis noted that no SMC satellites with on-orbit servicing features had been launched to date, Anderson said that SpaceLogistics’ space vehicle is compatible with approximately 80 percent of satellites on orbit, including many DoD satellites. And for those military satellites that are incompatible, future vehicles will be able to use robotic attachments to service them, he added.

While the second vehicle is entering production, Anderson said, SpaceLogistics is exploring its next generation of on-orbit servicing products. In the next iteration, a Mission Robotic Vehicle will launch along with a series of Mission Extension Pods. The pods will fan out until they are close to the client satellite in geostationary orbit, and then they will wait. The vehicle will make its way to each pod in turn and go through the process of attaching it to the client satellite, where it will be able to extend each satellite’s service life by augmenting propulsion. Once the pod is attached and working, the vehicle moves on to the next pod/satellite pair that needs to be attached.

In addition to installing the pods, the technology can also be used for basic satellite repairs, inspections and directly docking with on-orbit spacecraft.

Once installed, the pods are controlled by the customer. And when the satellite eventually reaches the end of its extended life, the pod will be able to remove the satellite from orbit or take it to the geosynchronous graveyard, preventing it from contributing to the growing threat of space debris.

SpaceLogistics’ next generation of satellite-servicing crafts is slated for launch in late 2023 or 2024.

Nathan Strout covers space, unmanned and intelligence systems for C4ISRNET.