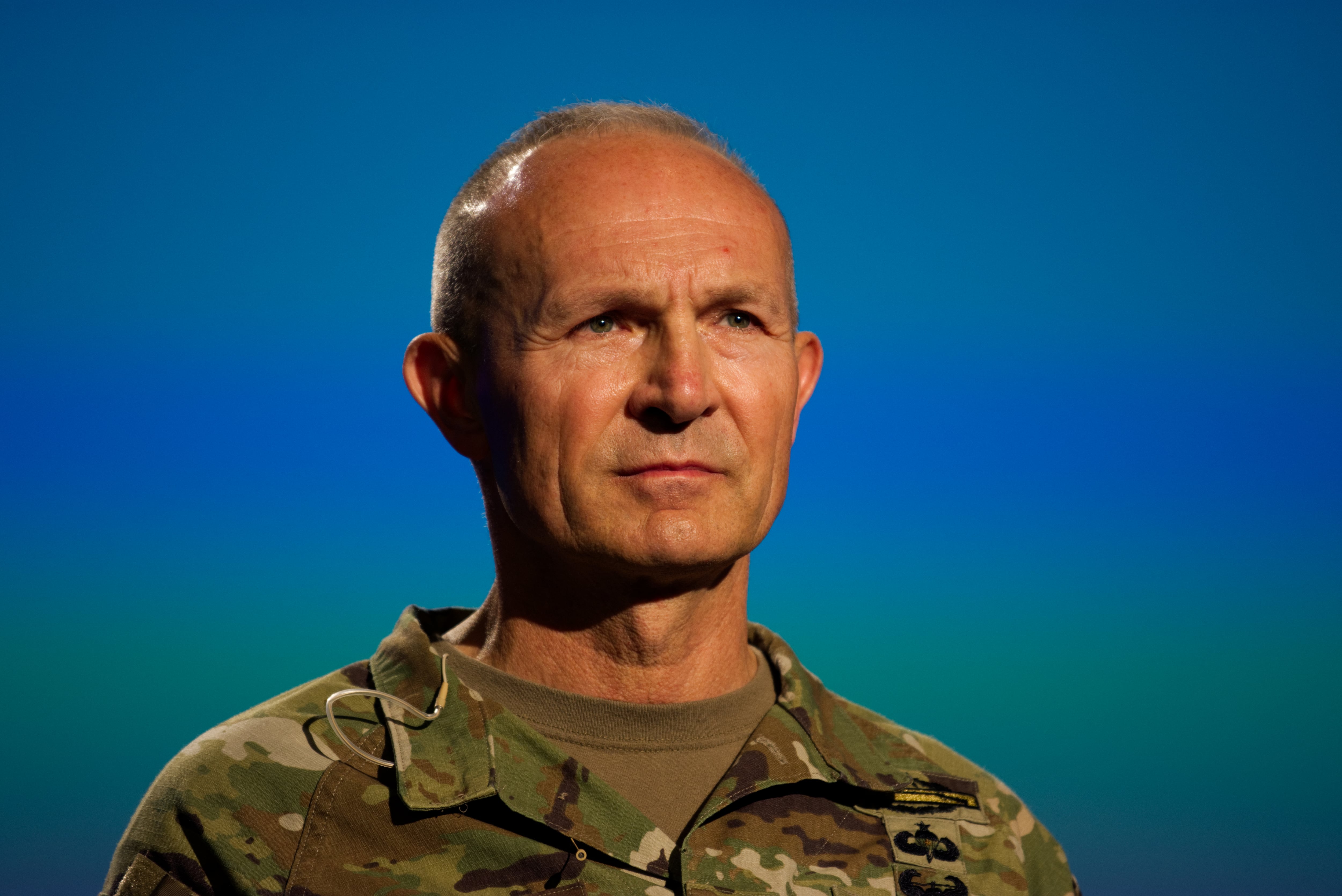

WASHINGTON — Maj. Gen. Paul Stanton leafed through his notebook.

He was sitting alone on stage during the last day of the Association of the U.S. Army’s annual conference, held in early October in Washington. The Army officer had just been asked about remarks made by the service’s newly sworn-in chief of staff, Gen. Randy George.

“Under continuous transformation, he did say the No. 1 priority and focus area is the network,” Stanton said, looking up from his notes and smiling. “Our Army senior leadership understands the significance of being able to move the right data to the right place at the right time.”

Stanton serves as both the commander of Fort Gordon and its Cyber Center of Excellence, a Georgia schoolhouse where troops are drilled on everything from electronic warfare to communications capabilities to cyberspace operations. The teachings there are increasingly important — especially so, after George named networking upgrades the Army’s most pressing modernization endeavor, citing lessons plucked from the battlefields of Eastern Europe.

While sophisticated, secure connectivity has for years been a focal point for the service, alongside other priorities such as long-range precision fires, air and missile defense, and aviation, it was not necessarily as high profile. Artillery, missile interceptors and helicopters have a splashy presence; the invisible tubes and tethers that enable military information sharing do not.

RELATED

But that does not minimize their importance.

“They’re providing the right prioritization, they’re providing the right guidance,” Stanton said. “They’re providing the right degree of resourcing in ways that we haven’t seen historically.”

‘Shoot, move and communicate’

As the U.S. Defense Department reshapes itself following decades spent in the Greater Middle East, it is assuming a new posture molded by Russia, China and the dangers posed by their digital-savvy forces. Both powers, much like the U.S., wield influential cyber weaponry and pour money into military-related science and technology efforts.

As a result, networks that are insulated from hackers and capable of reliably connecting front lines to headquarters, wherever they may be, are of utmost importance, according to U.S. military leaders.

The Army in fiscal 2023 sought $16.6 billion to fund cyber and information technology projects, about 10% of its total budget blueprint. About $9.8 billion was set aside for the network. Another $2 billion was earmarked for offensive and defensive cyber operations as well as cybersecurity maturation.

“The character of war is changing,” George said at the outset of his AUSA address. “It’s changing rapidly because disruptive technology is fundamentally altering how humans interact.”

“Soldiers need to shoot, move and communicate,” he added. “Technology should facilitate those fundamentals, not encumber them.”

One doesn’t have to look further than the Russia-Ukraine war for evidence, according to George, who said Moscow’s forces face the consequences of compromised networks and clunky command centers multiple times a day. In other words, aging connectivity and outdated outposts make for easy targeting.

American troops are now learning those lessons — just not “the hard way,” George said earlier at the conference.

“Antenna farms and endless server stacks are conspicuous and generate too much electromagnetic signature,” the chief of staff said. “If we slog around the battlefield with massive operation centers, which are difficult to set up, and often contractor-supported, we will get pounded.”

George’s preference to the network and its facets — security, reliability and flexibility — feels more like an evolution of previous thinking than an entirely new paradigm, both Lt. Gen. Maria Barrett, the head of Army Cyber Command, and Lt. Gen. John Morrison, a top uniformed IT official, told C4ISRNET.

George served as the Army vice chief of staff before assuming his current role.

“As the vice, the chief was really driving us in a direction to really get after how we simplify the network at the edge, make it resilient against a near peer and make something that can actually move,” Morrison said on the sidelines of AUSA.

“All of our modernization,” he added, “hinges on a network that is secure, defendable and maneuverable.”

Bigger and better

The demand for network innovation comes as the Army focuses on the division, not the brigade, as the unit of action.

The larger formation, made up of about 15,000 soldiers plus firepower, is thought more suited for war against Russia or China, where fighting will likely be scattered across vast distances and require a level of self-sufficiency. Such expectations will put significant strain on networks.

RELATED

“What underpins everything is a singular vision that Army senior leaders have for the network. The network has to evolve, it has to be flexible, it has to be simple,” Mark Kitz, the head of Program Executive Office Command, Control and Communications-Tactical, told C4ISRNET. “In order to do that, we’ve got to build into our programs the ability to get after those three things.”

The office and other organizations in May rolled out what’s known as the division-as-a-unit-of-action network design.

The initiative is meant to inform communications setups moving forward and, ultimately, free up soldiers under fire by reassigning more complicated networking tasks.

“I think underpinning a lot of this is our ability to be agile,” Kitz said, “and our ability to look at the network as a living, growing, evolving set of capabilities, whether that’s applications, whether that’s backhaul [satellite communications], whether that’s radios.”

“All of them have to evolve over time,” he added, “so we can leverage innovative technologies that we can reorganize and reconstitute based on how the Army wants to fight in the future.”

Colin Demarest was a reporter at C4ISRNET, where he covered military networks, cyber and IT. Colin had previously covered the Department of Energy and its National Nuclear Security Administration — namely Cold War cleanup and nuclear weapons development — for a daily newspaper in South Carolina. Colin is also an award-winning photographer.