TAMPA, Fla. — Developers need to build “ethical” artificial intelligence for military use, but that same technology must also explain what it does, according to the chief data officer of U.S. Special Operations Command.

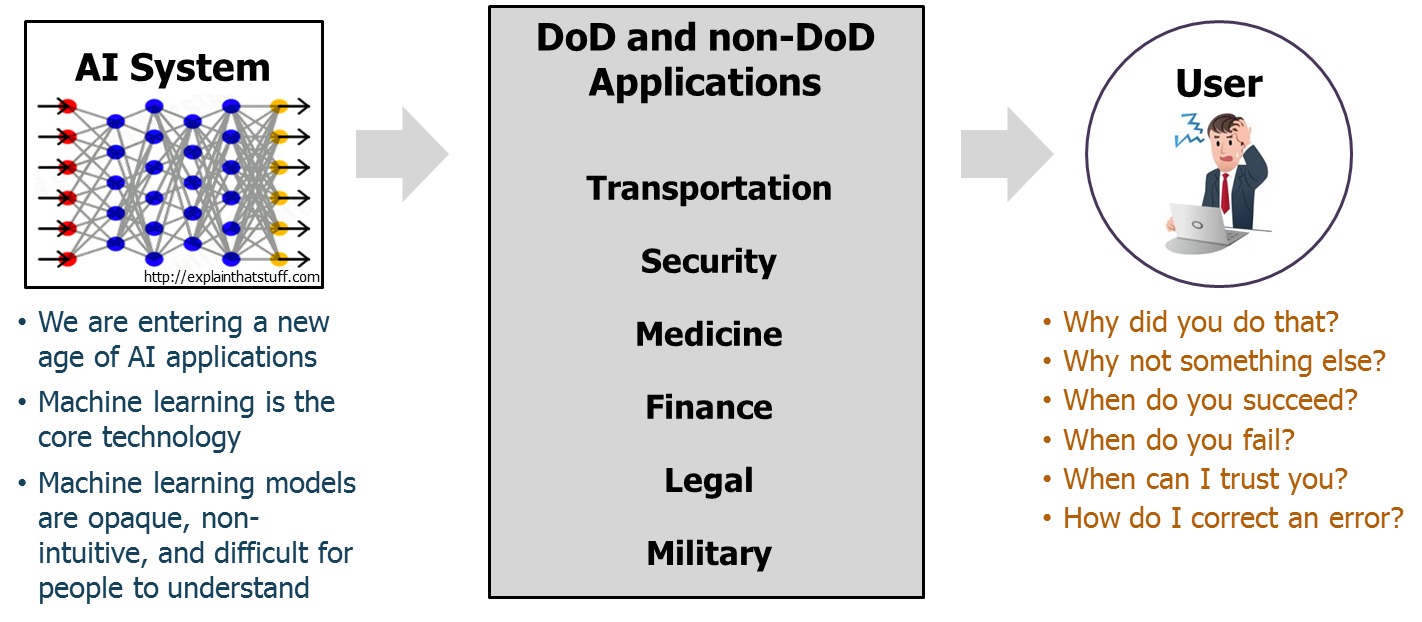

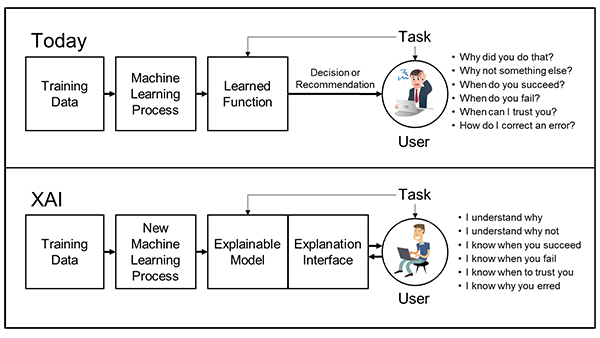

“At some point we’ve got to get to explainable AI,” Thomas Kenney said May 19 at the Special Operations Forces Industry Conference in Florida. “And explainable AI is a little bit different than saying ethical AI, because explainable AI means that algorithm needs to tell us why it made the decision it did.”

That’s because the speed of future warfare will mean AI talking to AI to make decisions that might not have a human at the helm, Kenney said.

This is no different than expecting a Navy SEAL team to explain its decision-making process following an overseas deployment, he explained.

“That’s essentially what we’re doing today from an AI ethics perspective,” he said. “We’re going back to the engineer and asking the engineer to explain: ‘Why’d you code that algorithm that way?’ ”

Instead, he added, the algorithm must explain to its user the decisions it makes, and the “explainability” factor will be “absolutely essential.”

“If they cannot explain to each other how they are making decisions programmatically, we’re never going to be able to win a strategic fight that is dominated by AI,” Kenney said.

Explainable AI isn’t an entirely new idea. The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency demonstrated some early capabilities in 2018, according to its website. That effort sought to simultaneously keep high-prediction accuracy with the algorithm while also delivering results that humans could understand and trust, DARPA has noted.

Notably, Kenney said, one of the areas in which SOCOM wants to improve is the “semantic layer” — or a means by which the command can deliver data in layperson’s terms.

“This is for the non-data scientists,” he said. “Advanced computing shouldn’t just be with the engineers. It should be with the [subject matter experts] on the battlefield every day.”

To do that, SOCOM needs a better way to inform mission command and fuse intelligence across multiple platforms and sources, he added.

The first step on the mission command front requires a quick way to see the status of its people and logistics. “We have to know where we are when the phone call comes in and says this is what we need to do,” Kenney said.

He pointed to lessons on information operations coming out of Ukraine as a prime example, with social media often providing as good or better information than Ukraine’s military intelligence agencies. But without a way to harness that data by fusing intelligence from various points, it’s difficult to create a complete picture.

To tackle that problem, mission command systems must have an application programming interface design built-in, an open architecture that is platform-agnostic, and — most important for intelligence fusion — real-time data integration, he said.

That real-time data is critical because operators can’t work with outdated information or pause a mission for a refresh.

At another panel during the conference, Mark Taylor, who serves as SOCOM’s chief technical officer, pointed to the concept of a hybrid cloud as one solution. But since the government uses several vendors for its cloud services, he said, software and application developers need to bake into their products ways for the command to operate on multiple clouds.

“It’s like that ‘Star Trek’ elevator that goes up and sideways,” Taylor said, adding that the command is looking for ways to perform computing tasks “no longer bound by the environment that it’s in.”

Todd South has written about crime, courts, government and the military for multiple publications since 2004 and was named a 2014 Pulitzer finalist for a co-written project on witness intimidation. Todd is a Marine veteran of the Iraq War.